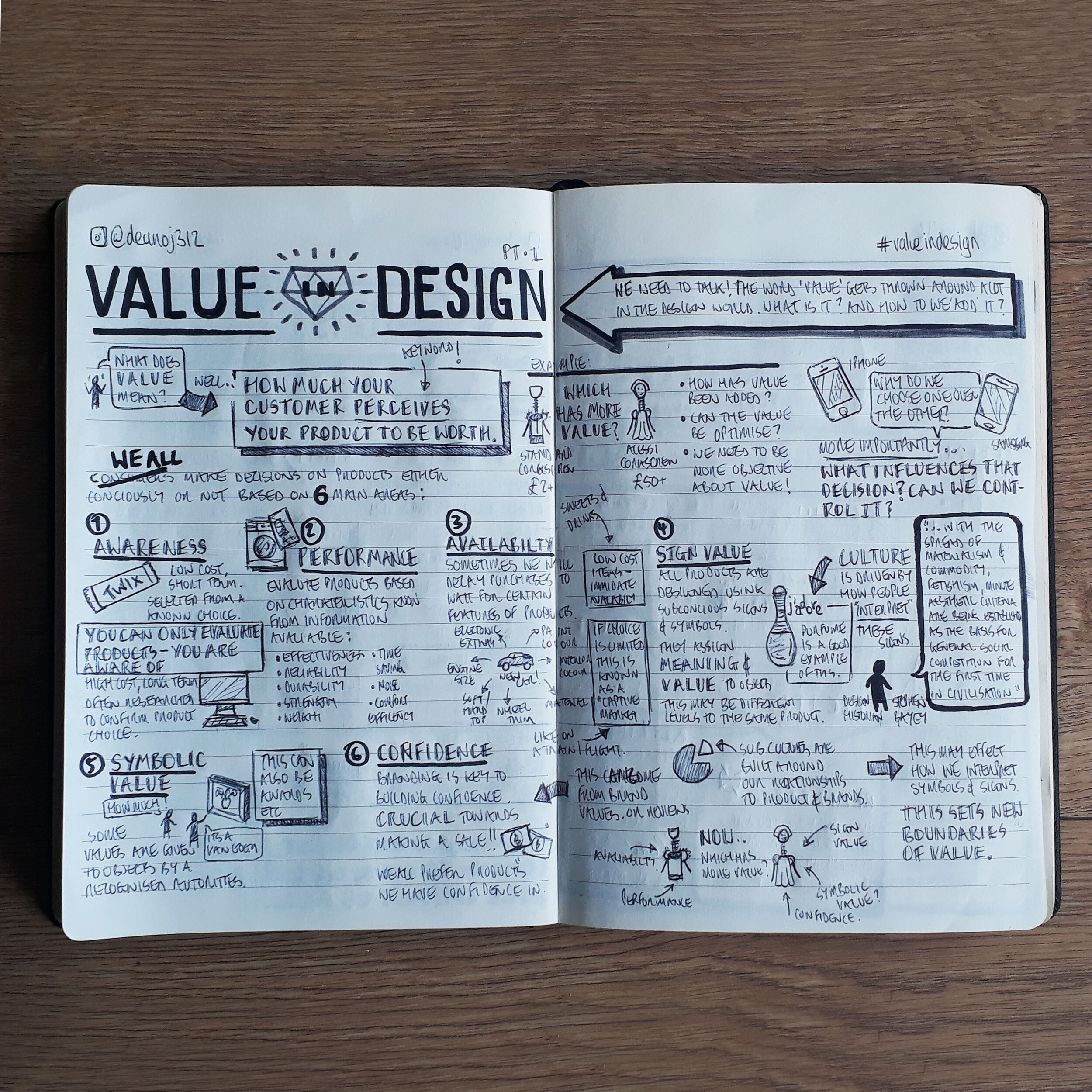

Value in Design

Image courtesy of @sharonmccutcheon via Unsplash.

Reading time: 4 mins

We need to talk about Value…

As creative professionals, we talk about value a lot during the design process, sometimes without even knowing it. Everyone has a different perspective on what value is and how to get it. We all know that perspectives are subjective, and subjectivity can be the enemy of a good and happy design process.

More importantly, values are emotional hooks for consumers, and as Douglas Davis says in his book, Creative Strategy and The Business of Design, “Values, at their core, are emotional. And emotions activate behaviour. Values have worth. Values go far beyond usefulness to have emotional meaning. They are different for every person, so values are personal. Values answer the question: Why should I care?”. Values are key to creating your products unique selling point, hooking a consumer to make a purchase.

So, How do we remove the subjectivity from the discussion of value?

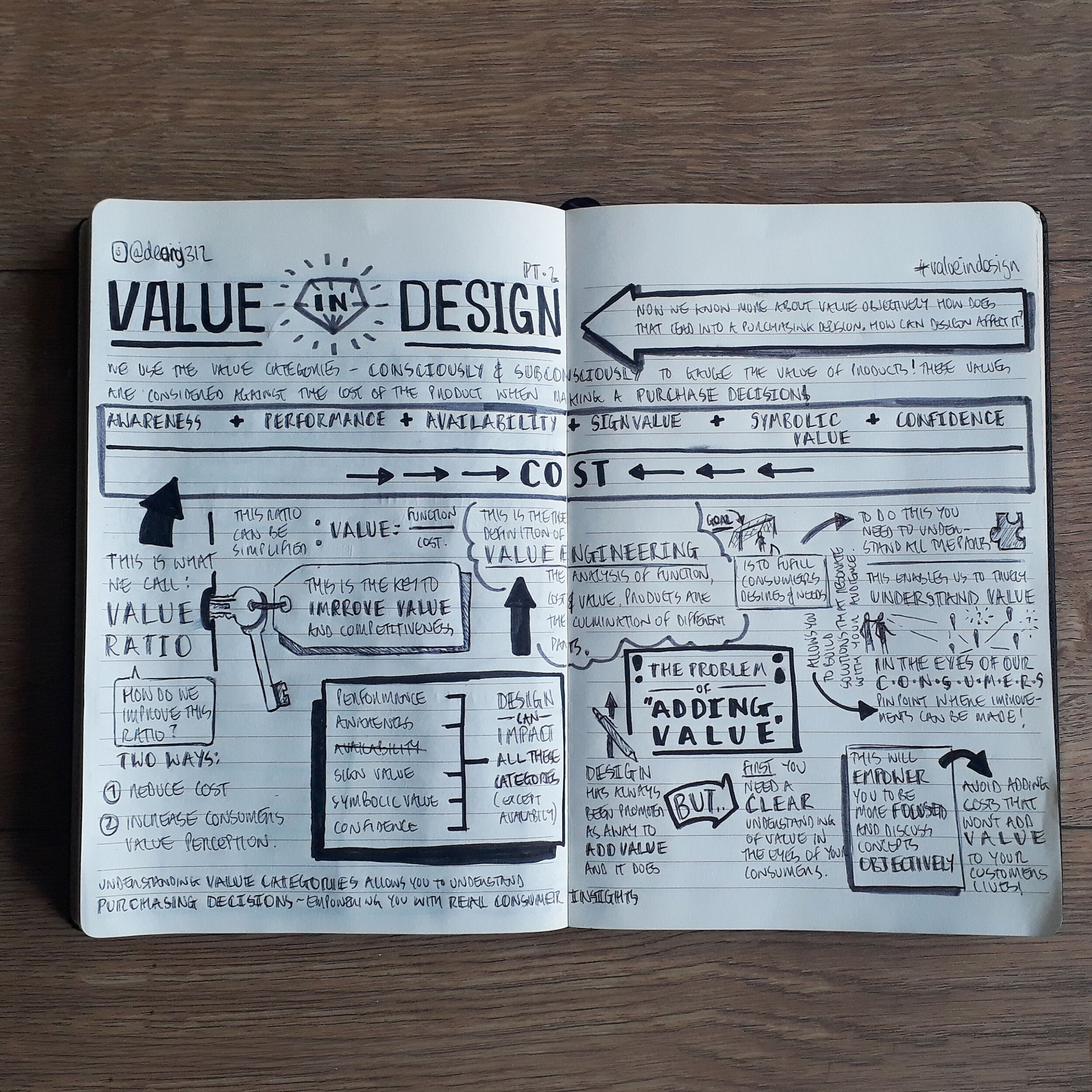

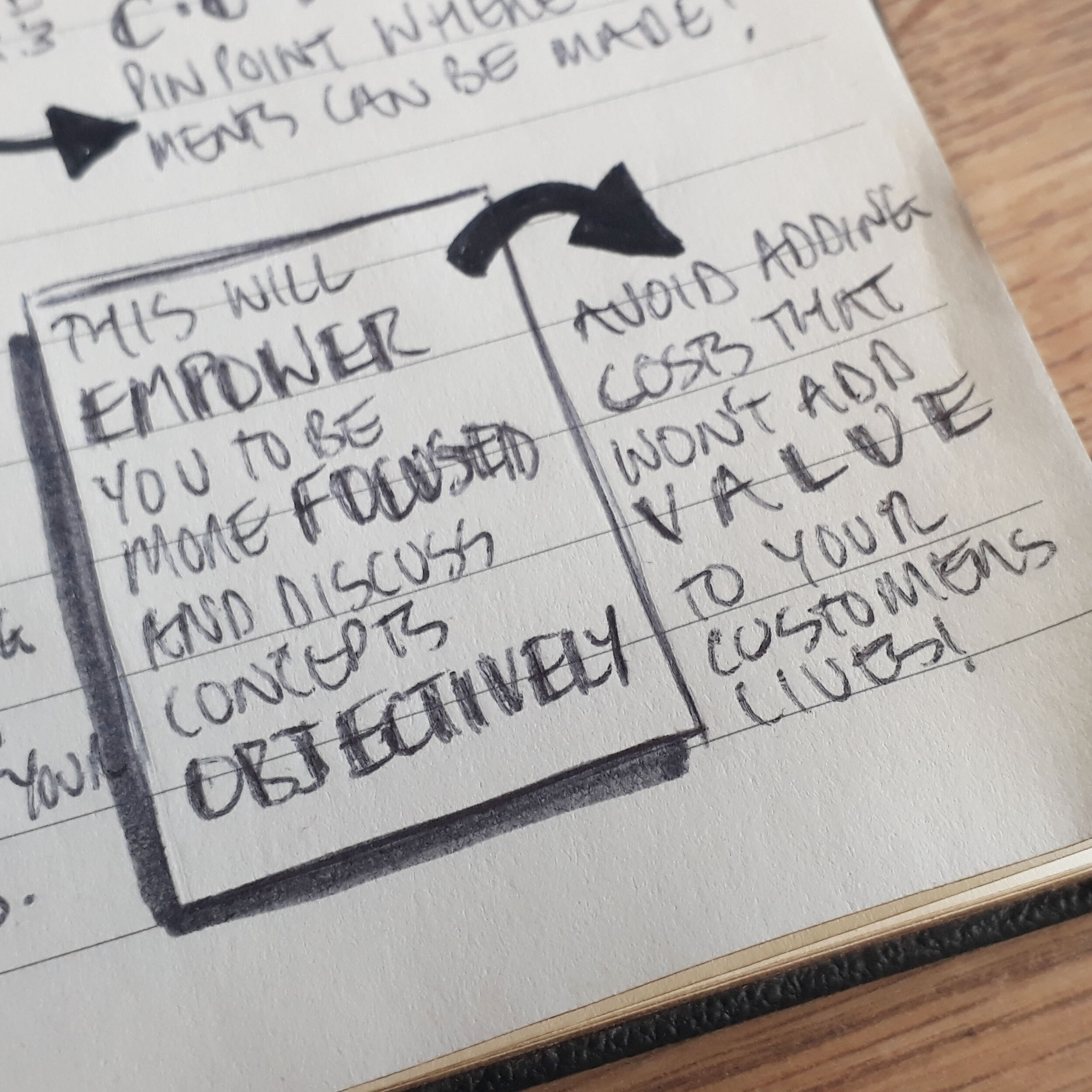

First, we define what value is. That is the focus of this blog article, which will be the first in a two-part series. The focus of this first part is establishing a foundation of information about value, breaking down the subjective into objective, easy-to-understand parts, giving you definitions, value categories and how this relates to a consumer decision to make a purchase through building a value ratio and the big problem with the phrase ‘adding value’ when designing. The main goal of this blog is to empower you to talk more objectively about value.

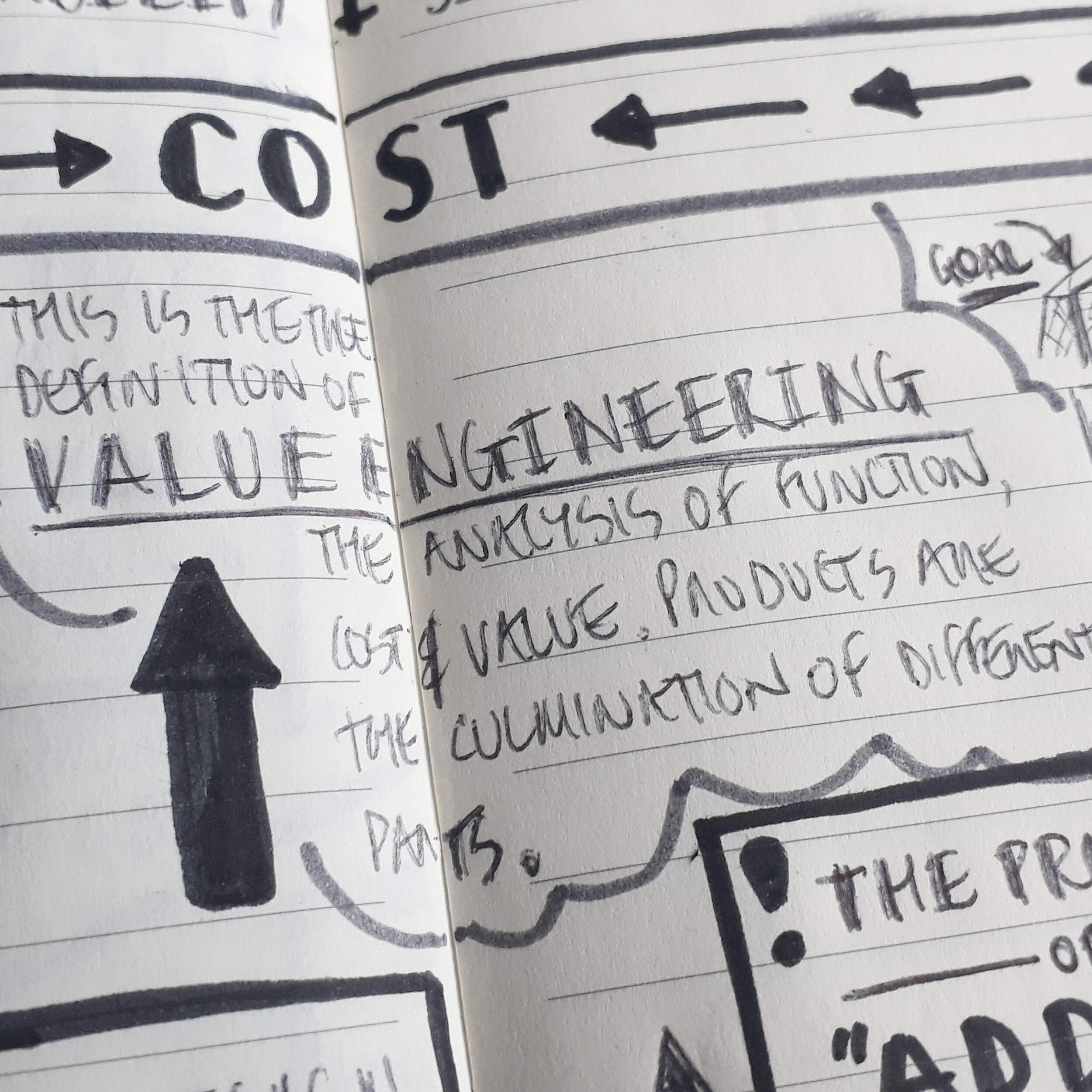

Let’s start with the true definition of value. Many people believe value is about being cheap, getting the most bang for your buck, however this is a common misconception about value in design.

The true definition of value is how much your customer perceives your product to be worth and not what it is actually worth.

As consumer we make ‘value-based’ decisions all the time when buying products. Why do we pick one product over another?

A good example of this is the two smartphone giants Samsung and Apple.

When you break down the products objectively, based on facts and figures on paper, nine times out of ten, Samsung wins! They’ve been market leaders in technology for decades - recently, Apple even bought their OLED screens for their iPhone X from Samsung. So why do some people still choose Apple?

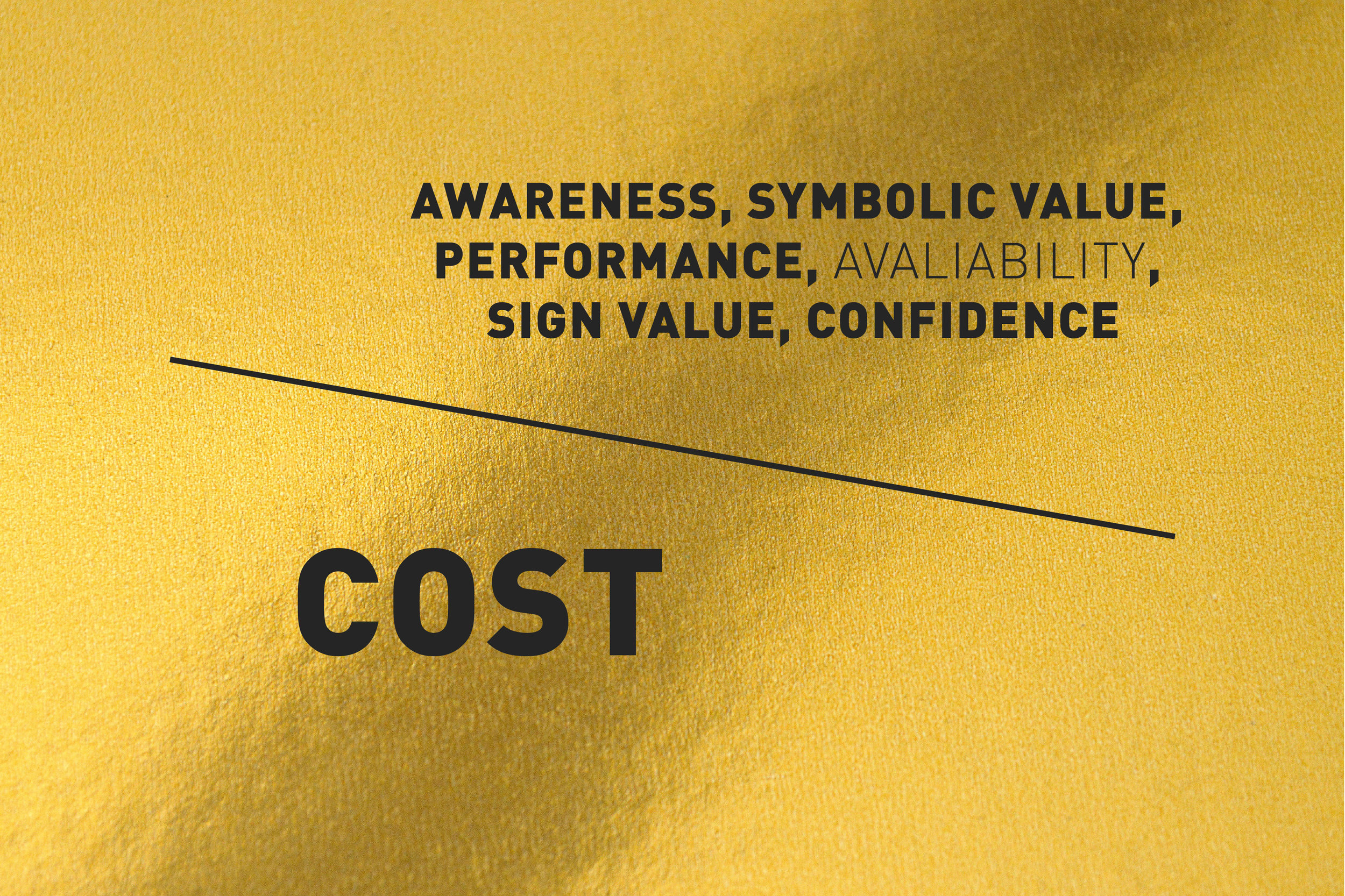

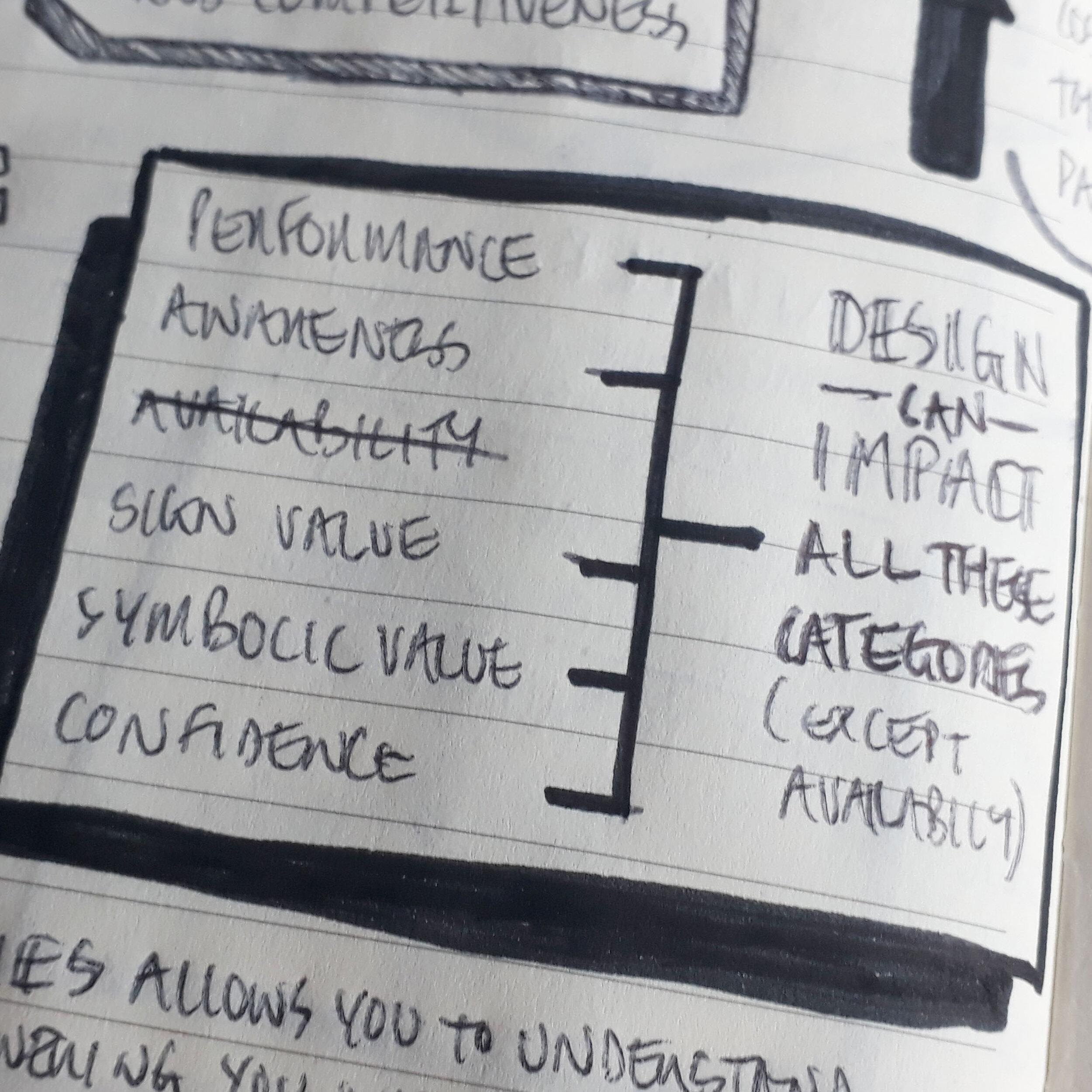

Value can be broken down into six categories: Awareness, Performance, Availability, Sign Value, Symbolic Values and Confidence. In the minds of consumers, this reasoning can be both conscious and subconscious.

Understanding these six categories is the key to understanding why consumers pick one product over another. So let’s break them down to get a better understanding of how they work:

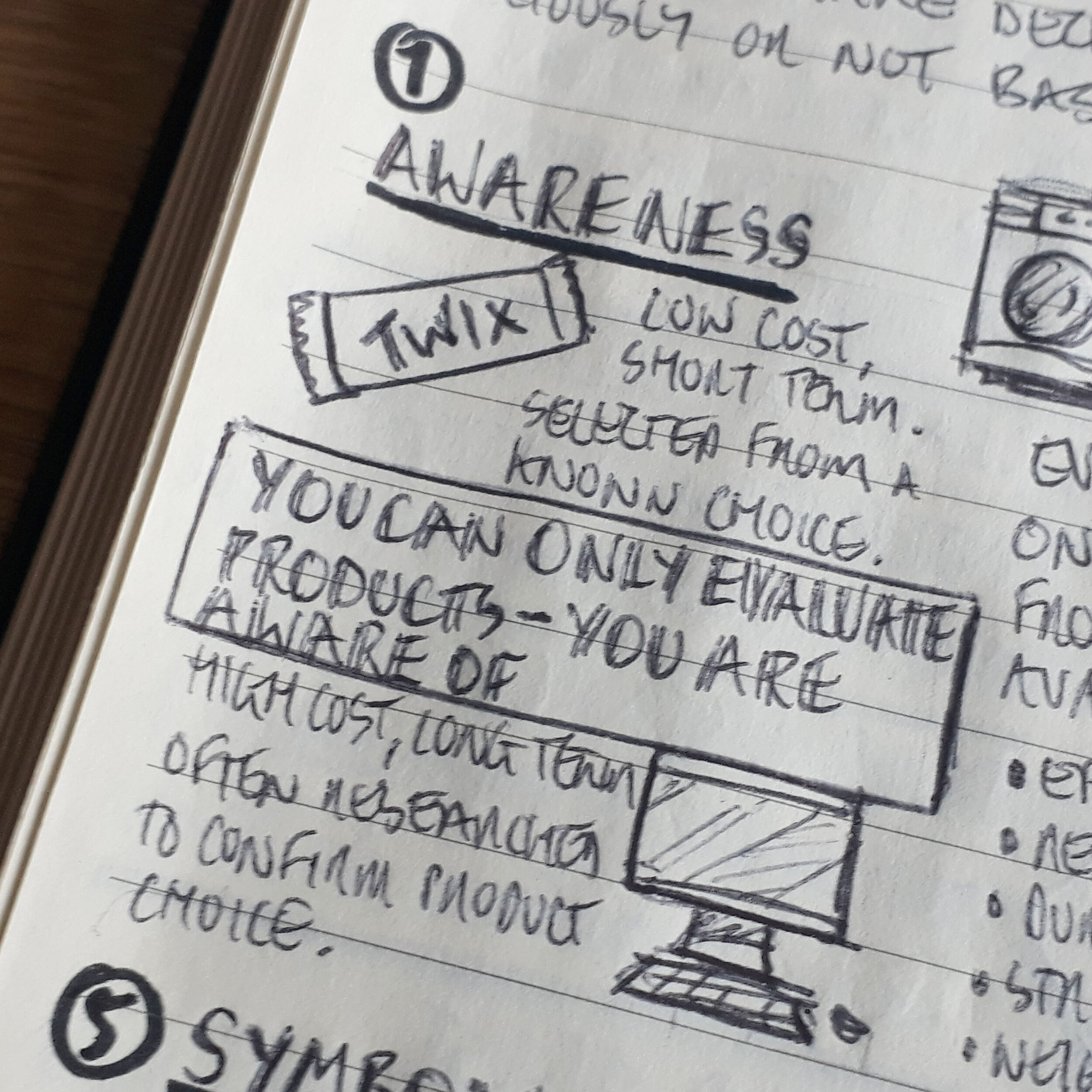

Awareness

Consumers can only evaluate products that they are aware of, which is the reason we have marketing. We can find out more information about products than we ever could, and this information is pretty much available all the time to a lot of people, since we have smartphones on us at all times.

Normally, low cost items or short-term purchases are selected from a known product choice, like chocolate bars, and high cost items or long-term purchases are often thoroughly researched beforehand to confirm a choice. Just think about the last time you bought a laptop or a computer - how long did it take you to come to that conclusion, and how much research did you do?

Advertising is still the best way to raise awareness in the modern market, but this is changing, as we are becoming more connected and more focused on individualism - the old paradigm of ‘word of mouth’ is becoming more prominent.

A good example of this kind of advertising is Netflix, which become more and more reliant on ‘word of mouth’ recommendations between groups. Think about it - do you remember seeing formal advertising for Bird Box, Tidying up with Marie Kondo or Conversation with a Serial Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes? I don’t.

But how many of your friends recommended these shows to you, and how often did they pop up in your Facebook and IG feeds?

It’s certainly true that Netflix fuelled quite a lot of the buzz initially, on their own social media channels, but once the first few people started watching, the memes spread like wildfire. Going viral is simply a technologically-powered version of word of mouth, and something to consider when looking at your product’s value to your consumers.

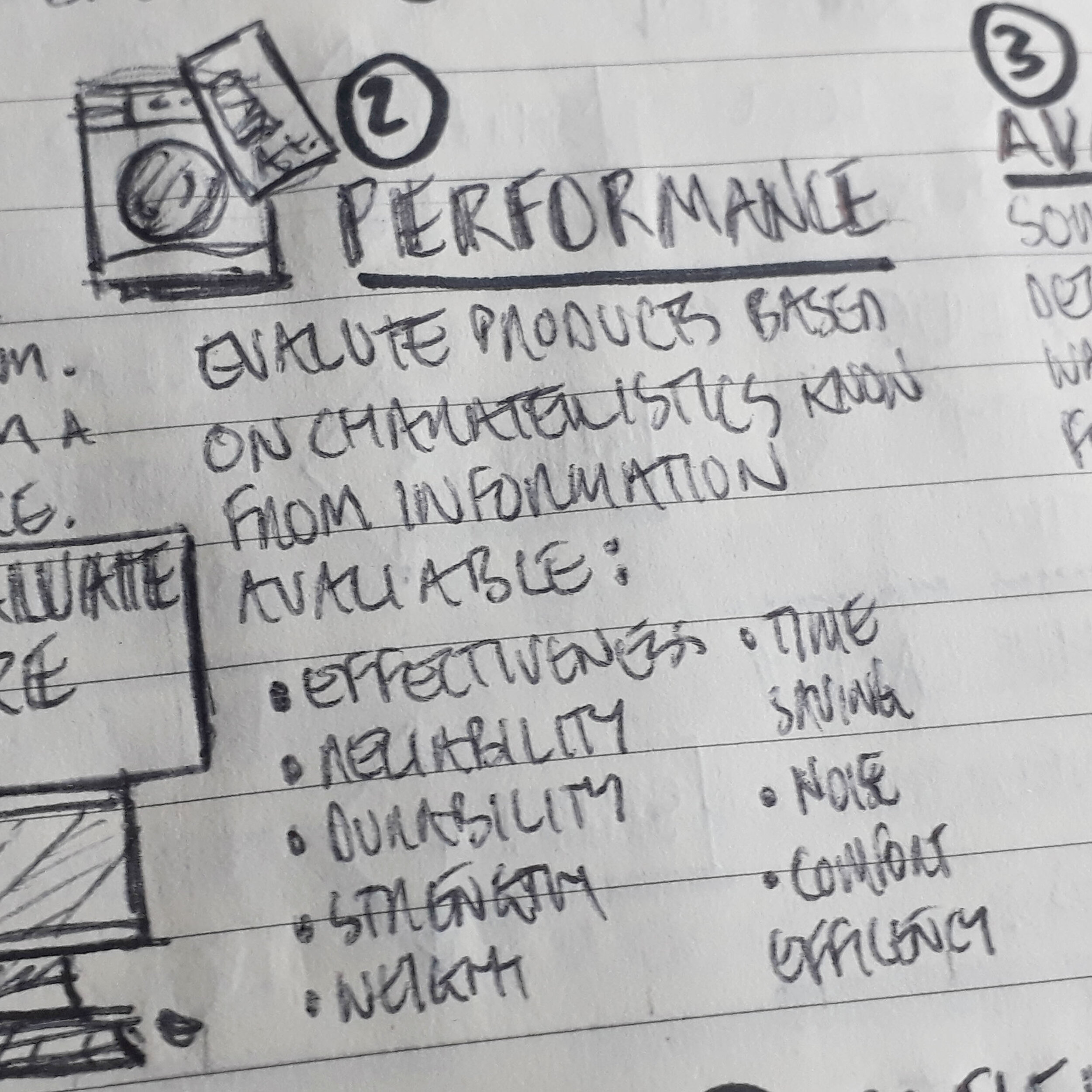

Performance

This category is one of the most objective ones. Consumers can weigh up the performance of product based on information such as reliability, durability, strength, effectiveness, weight, speed, noise, efficiency, and comfort (this list is certainly not exhaustive - product/service features change depending on the industry, and the product).

A good example of leveraging value in performance to consumers is with household electronic items like fridges and washing machines. They seek to affect consumers’ purchasing decisions by providing the information that they know their consumers will want, like the energy rating or how long a full wash-load takes.

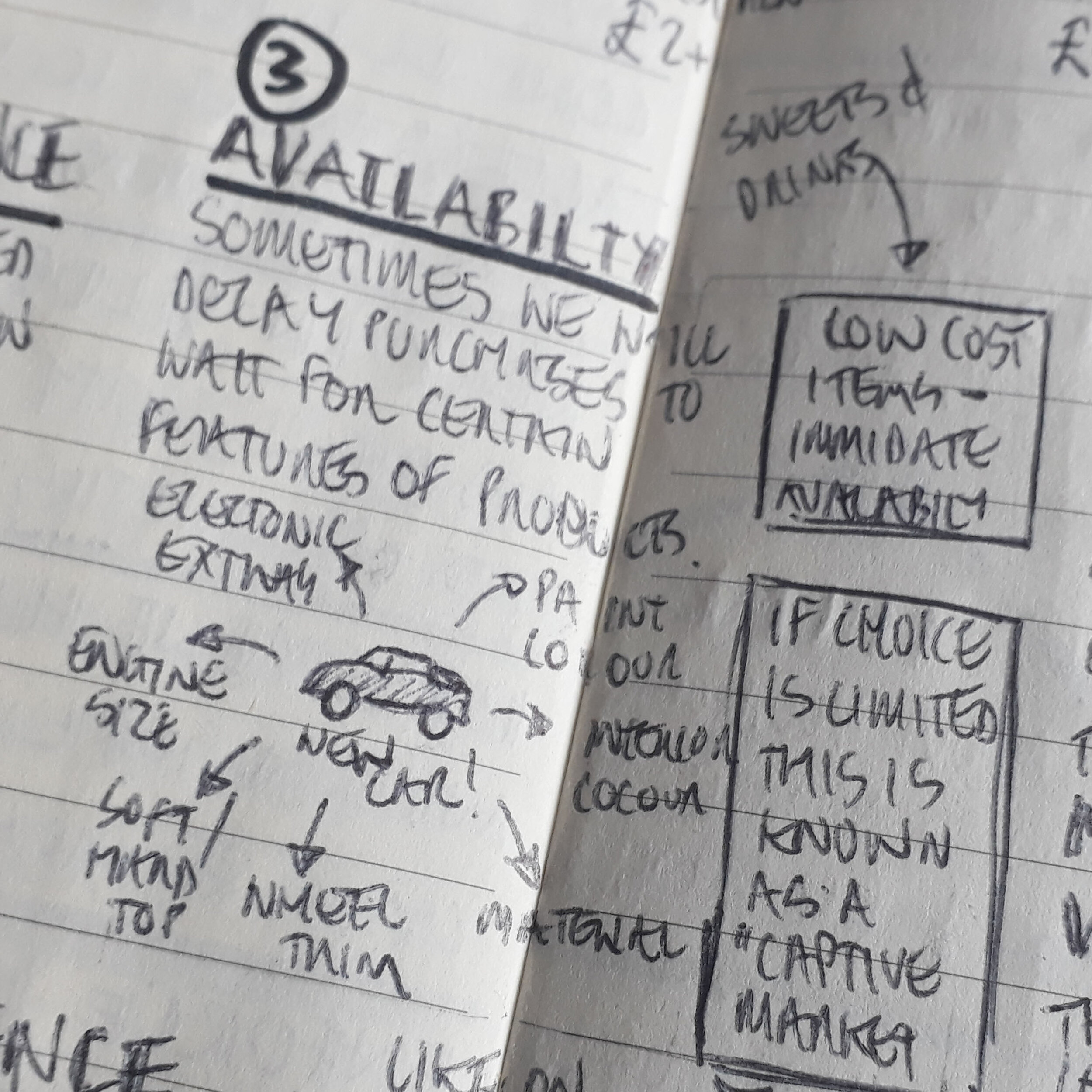

Availability

Sometimes, consumers will delay purchases to wait for certain products or features.

A good example of this is buying a new car. You may decide to wait for your dealership to deliver the car to your specific desires, which could be paint colour, interior finishes, wheel trims, engine size or electronic extras.

However, less important and lower cost products like snacks and drinks are based on immediate availability and short term gains, like quenching thirst or postponing hunger.

Sometimes, your availability to make a choice may be limited, such as if you are on a flight - your choice is limited to what is available from the trolley. The audience of these sorts of products is what is known as a captive market. There is very limited choice, and these products usually come with an increased price tag.

Confidence

We all prefer products we have confidence in, and the key to building confidence is branding. Confidence can be communicated through various brand values: quality, heritage, even reputation. Confidence building through branding is crucial for consumers to make that decision to make a purchase.

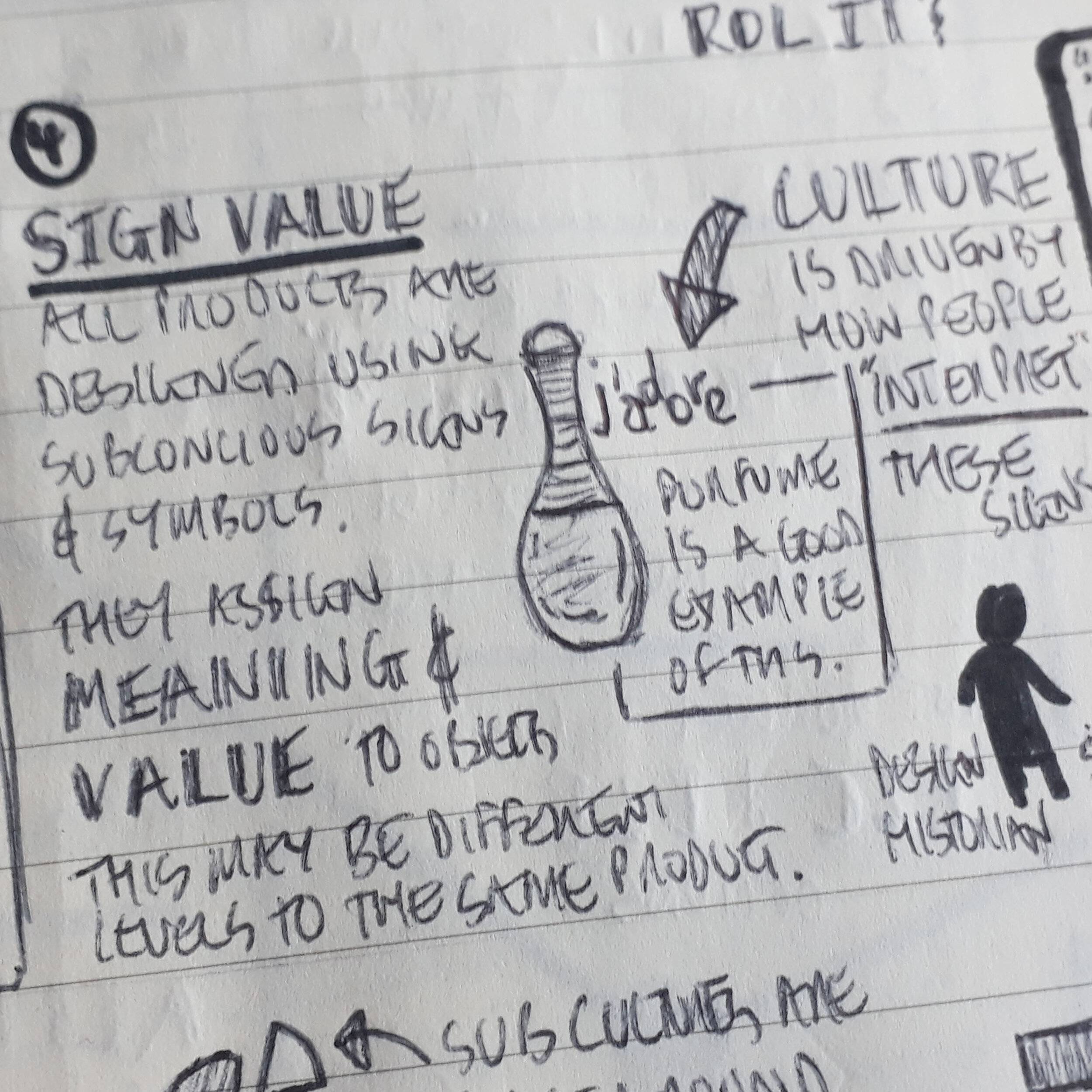

Sign Value

Every product has been designed using a range of established sign and symbols.

These are sometimes subtle cues which are used to assign meaning and value to objects.

This can be subjective and can very, depending on culture and popular trends. These give our designs status and meaning.

Modern culture is driven by how we interpret these signs and symbols, with sub cultures being defined by our relationships to brands and products. Different cultures set their own boundaries of value, and understanding these boundaries can be the key to producing a best-selling product.

A great example of this is how perfume and cologne companies operate, with their dependence on celebrity collaboration, elaborate packaging, and the ethereal ‘moving-moodboard’ adverts on television. The adverts may seem like nonsense, but they work - the fragrance industry is worth about $92 billion!

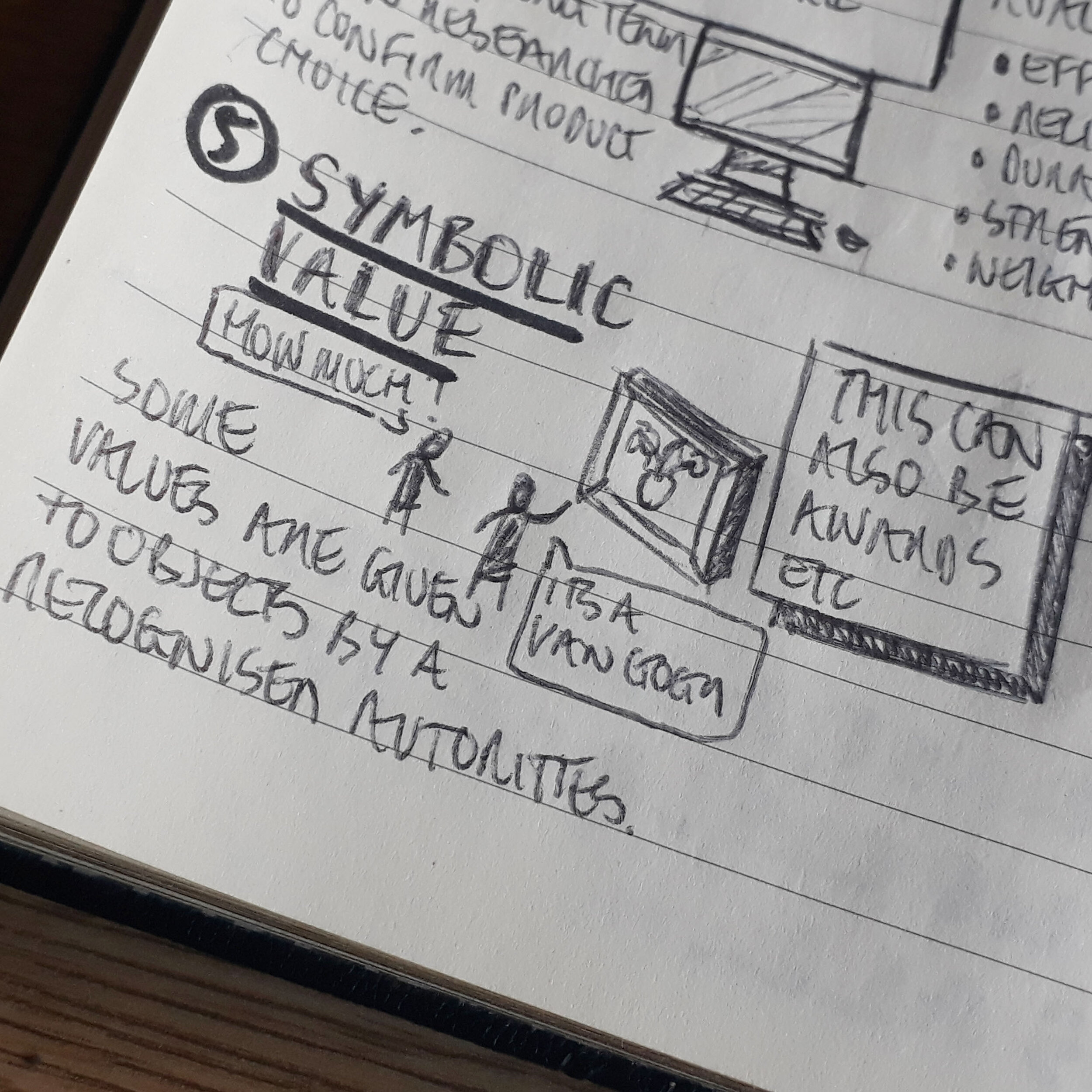

Symbolic Value

This is a pretty simple one: symbolic value is the value given to an object by a recognised authority. A good example of this is art - look at the rise in popularity and value of artists like Banksy. Another example could be how consumers want to own the same products celebrities use. This can be anything from cosmetics, clothing or even electronics.

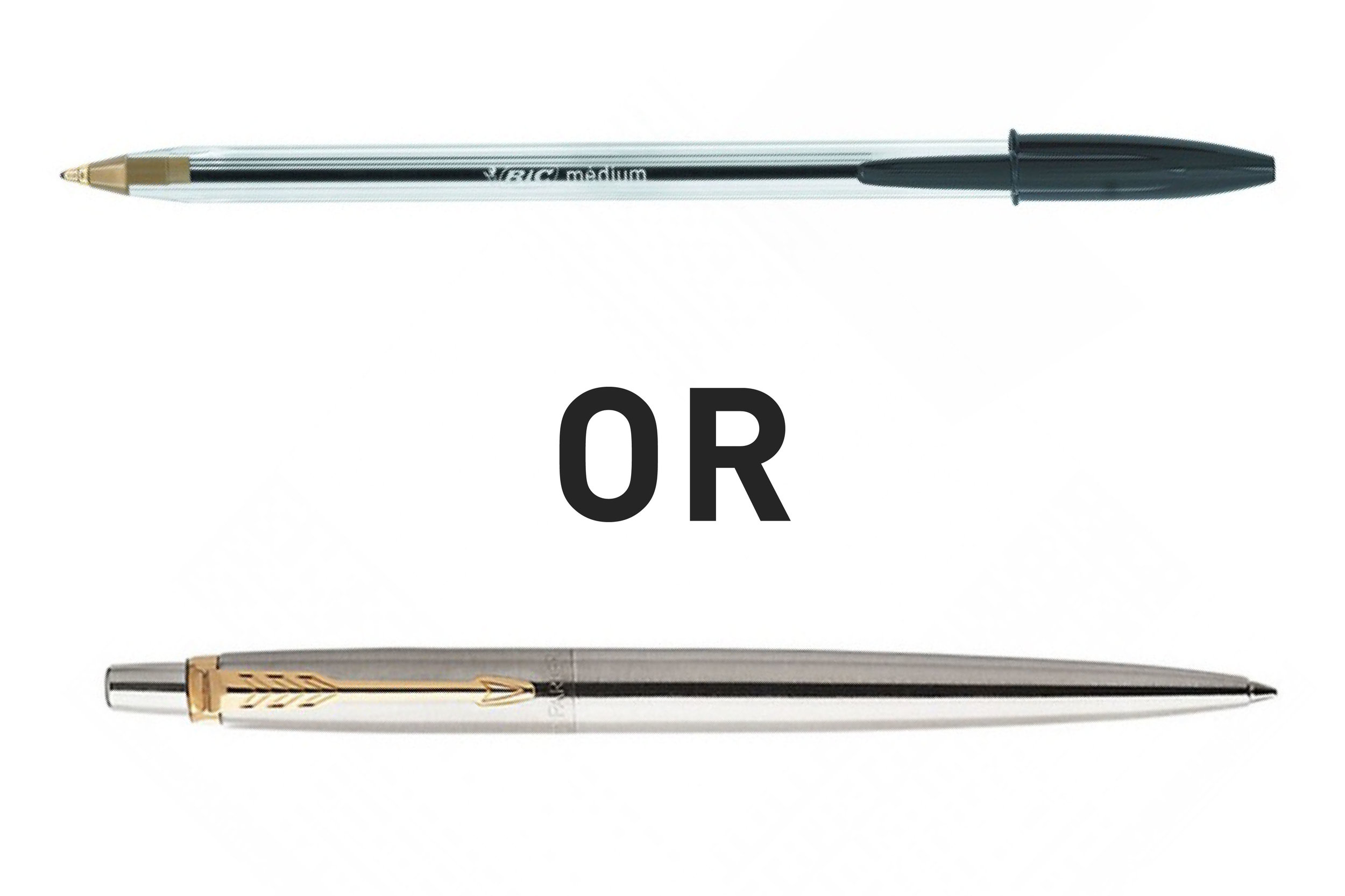

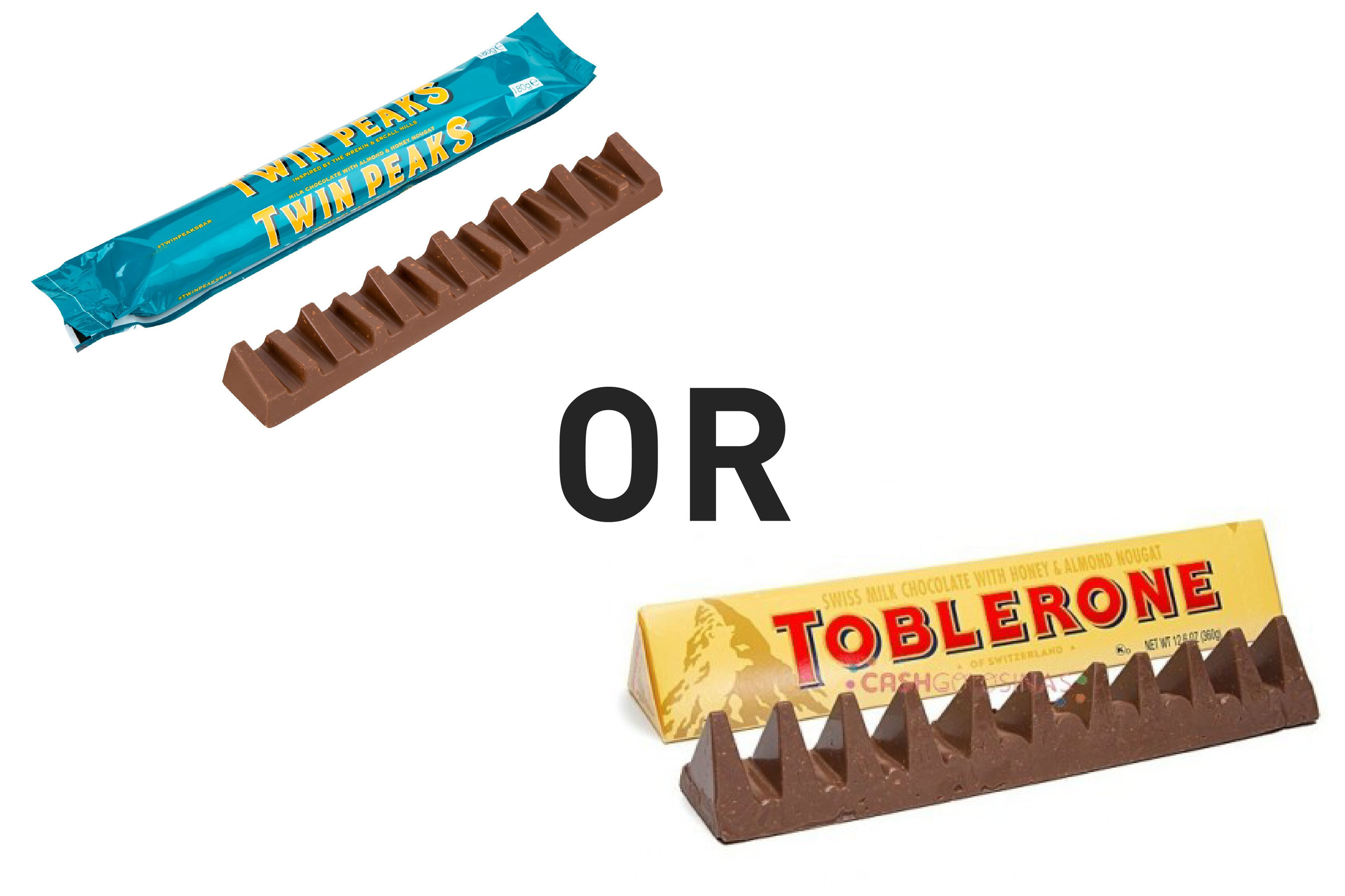

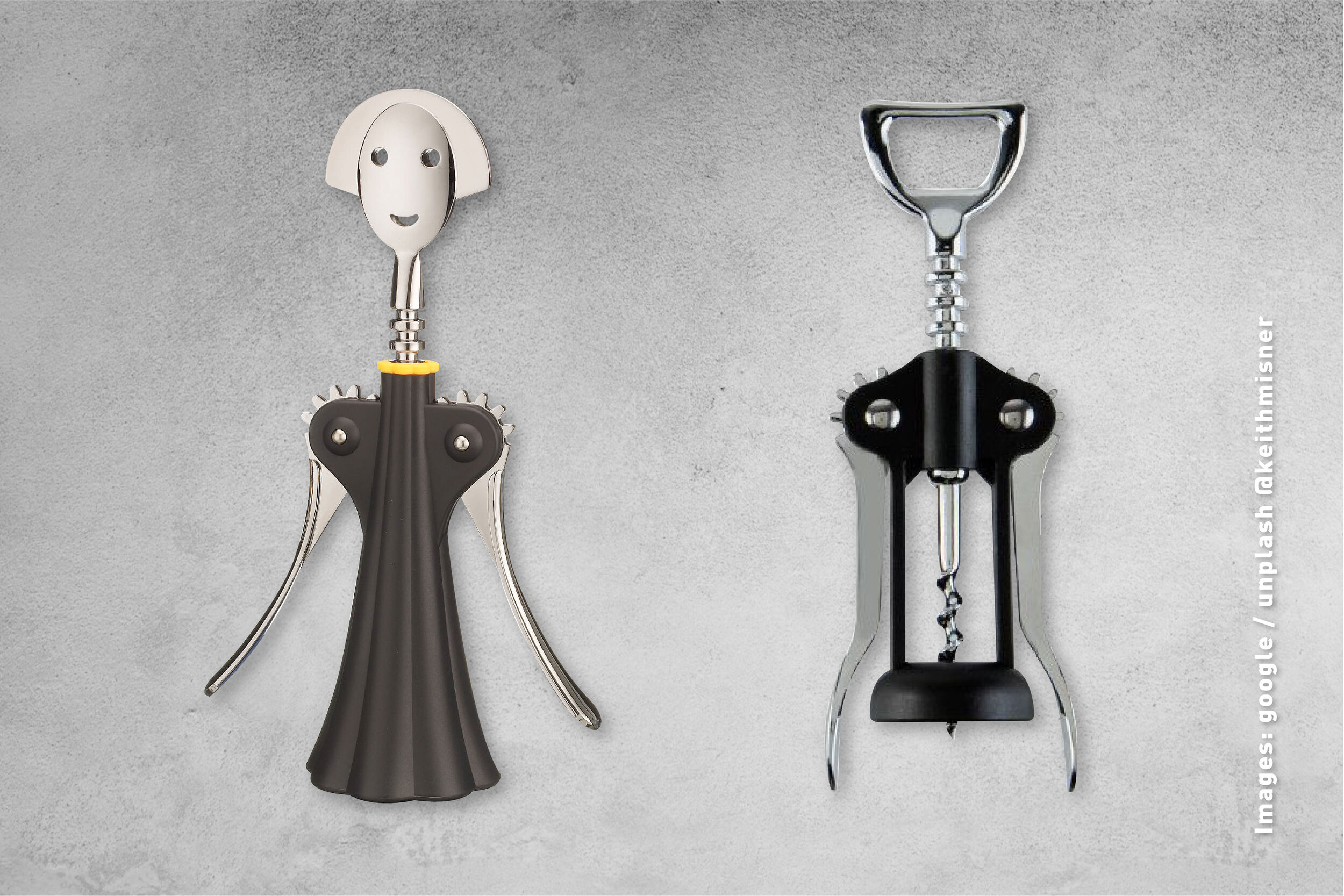

Now we know more about the categories that make up value, think about the like-for-like products below.

Which do you think has more value, and how have they leveraged these different categories for their products?:

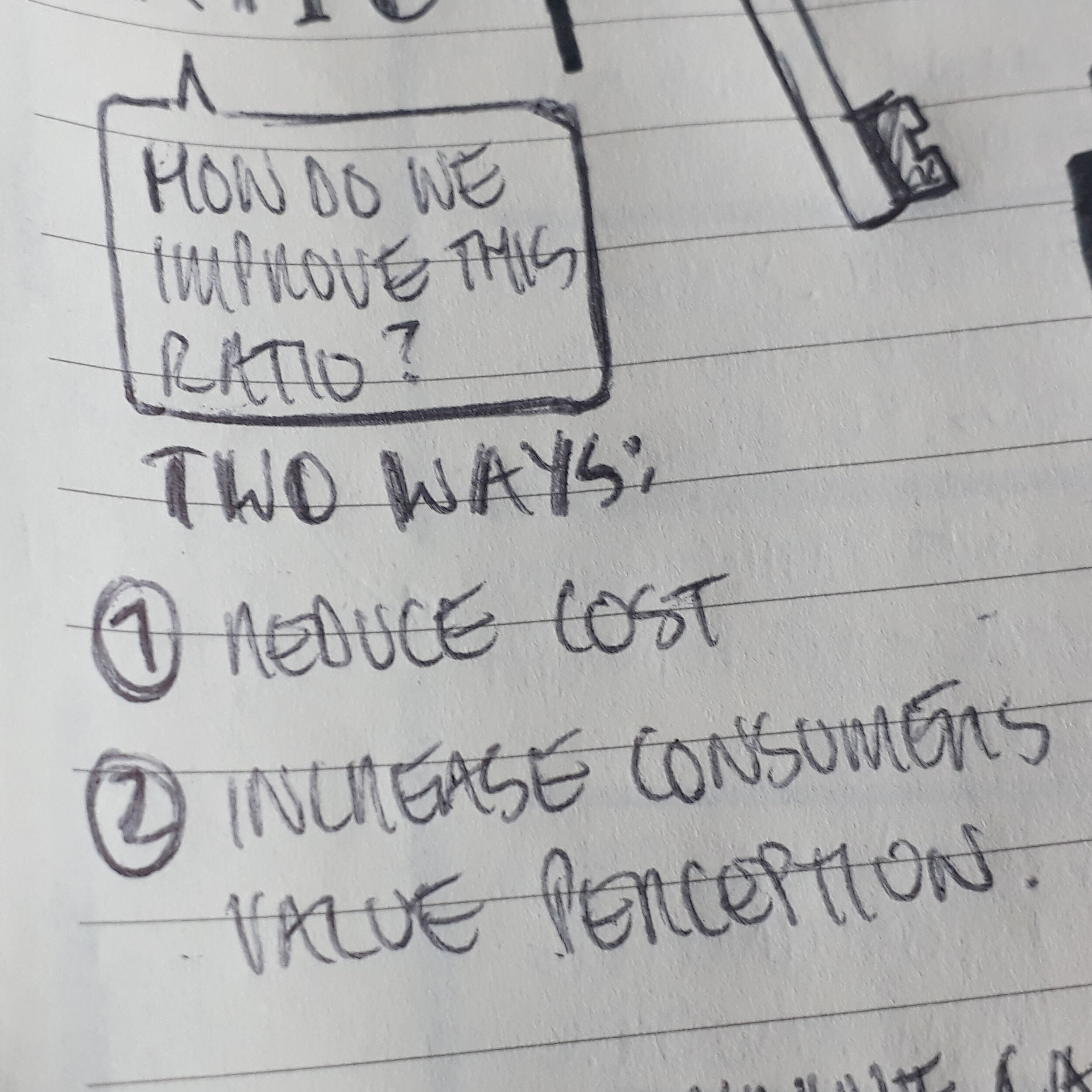

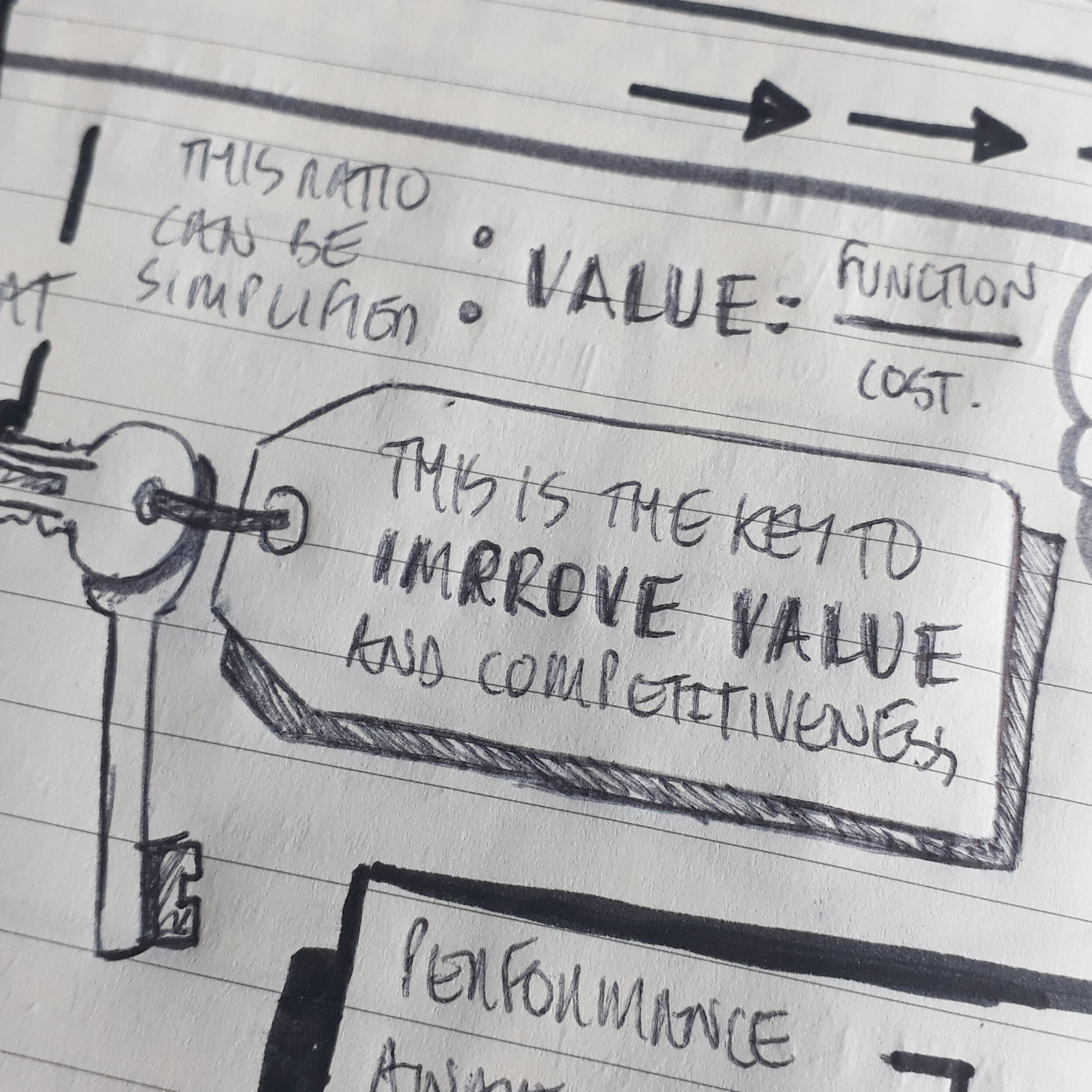

We make these decisions everyday without even thinking about it. We weigh up all the values and then decide if the product is worth its designated price. That gives you what we call a Value Ratio, an objective way of looking at the subjective.

It can be used to develop a more competitive product and improve the value in the minds of consumers. There are two ways to improve this ratio: the first is to reduce the cost of the product, and the second is to increase the consumer value perception of the product.

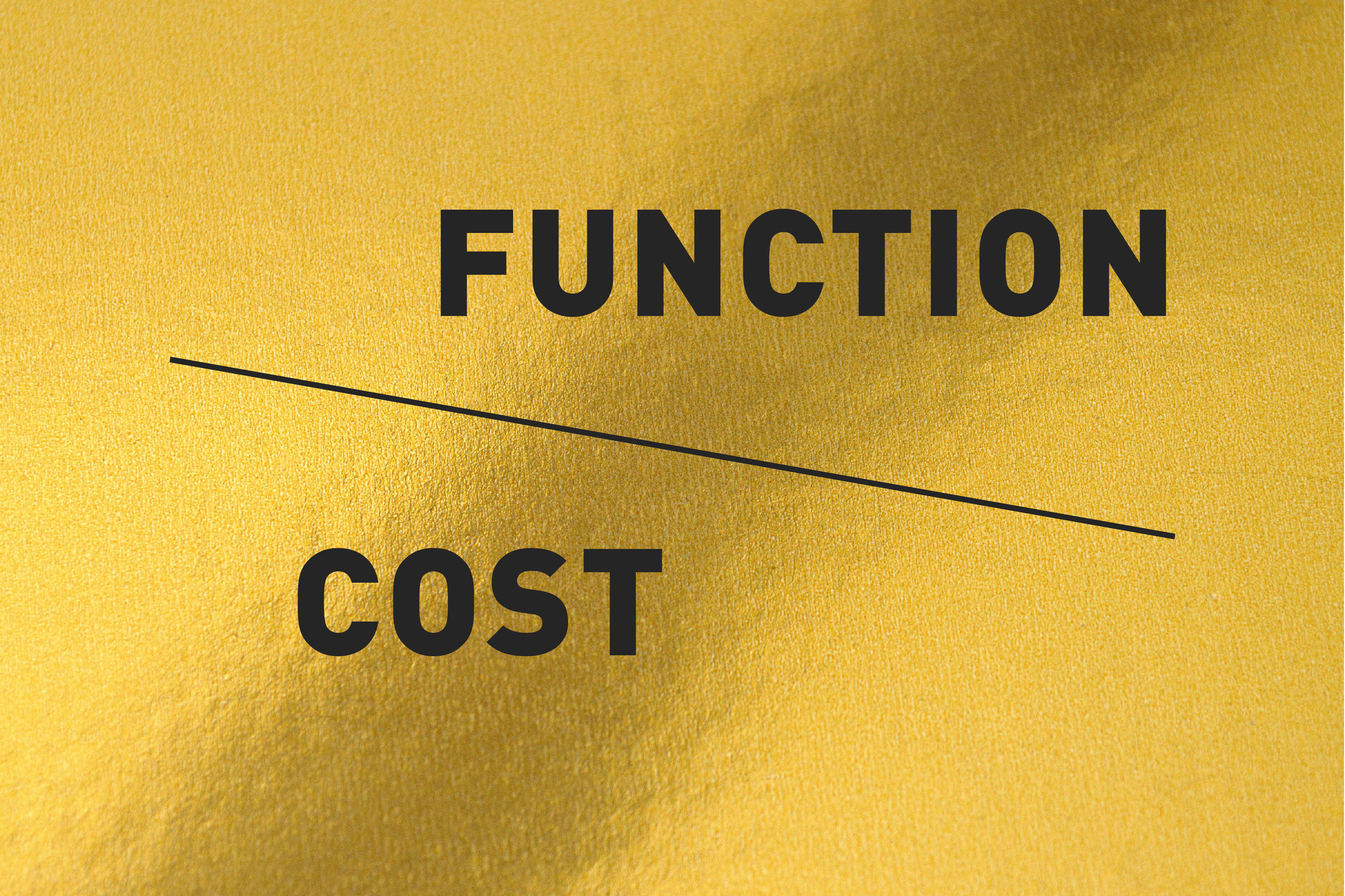

From a designer’s point of view, design can have an impact on five of the six values categories (the exception being availability). The analysis and development of functions, cost and value is called Value Engineering.

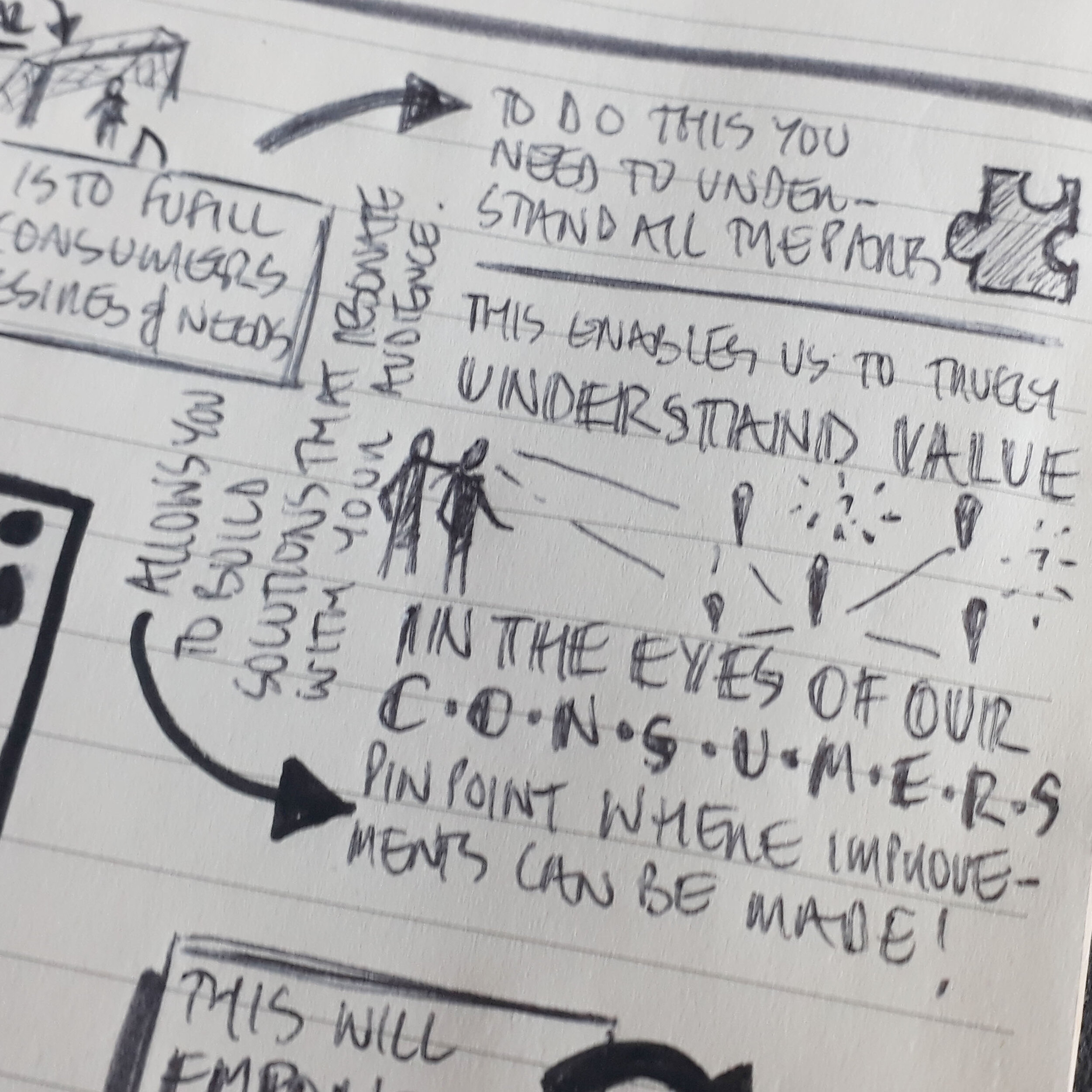

Each part of the design is studied to see how that component is delivering value to the overall consumer need and desires against the cost of those components. These studies enable us to gain a true understanding of products current and potential value for consumers and most importantly we can pinpoint where designs can be improved.

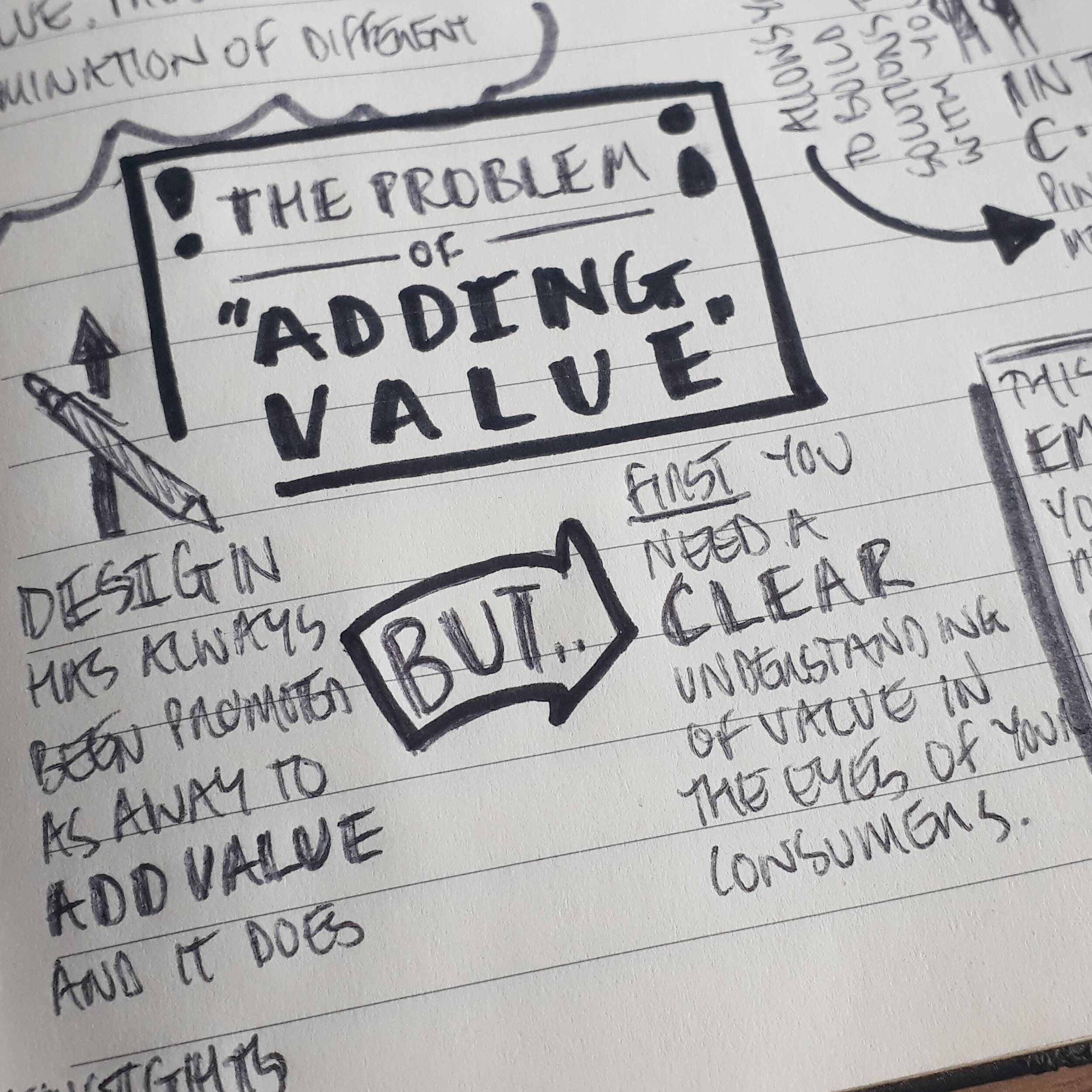

For many, design has been seen as a way to ‘add value’, and it does, but in order to do that effectively and efficiently, you need to understand your consumers’ perception of value.

If not, you will find your design will lack focus, and you will fall into an abyss of subjective development loops, making decisions that likely won't add value to your design.

To understand your consumers’ perception of value, you need to know who your customers are, in as many ways as you can - this is where design

and marketing start to merge.

Hopefully, now you can start to see a thread flowing through this article - how a detailed understanding of value categories, in relation to your own design, can allow you to understand purchasing decisions, which links to real consumer insights on how they perceive the value in your design.

As a result, you should now be able to improve your ability to discuss and manipulate value within your design focusing in on values that resonate with your consumers.

Now we understand the parts of the value ratio, it’s time to focus on how we can manipulate the value ratio outlined in part one to create better design solutions for our clients and businesses.

Now we are masters of discussing value in an objective way, it’s time to focus that knowledge into manipulating the value ratio to improve the perception of value in the eyes of your customers.

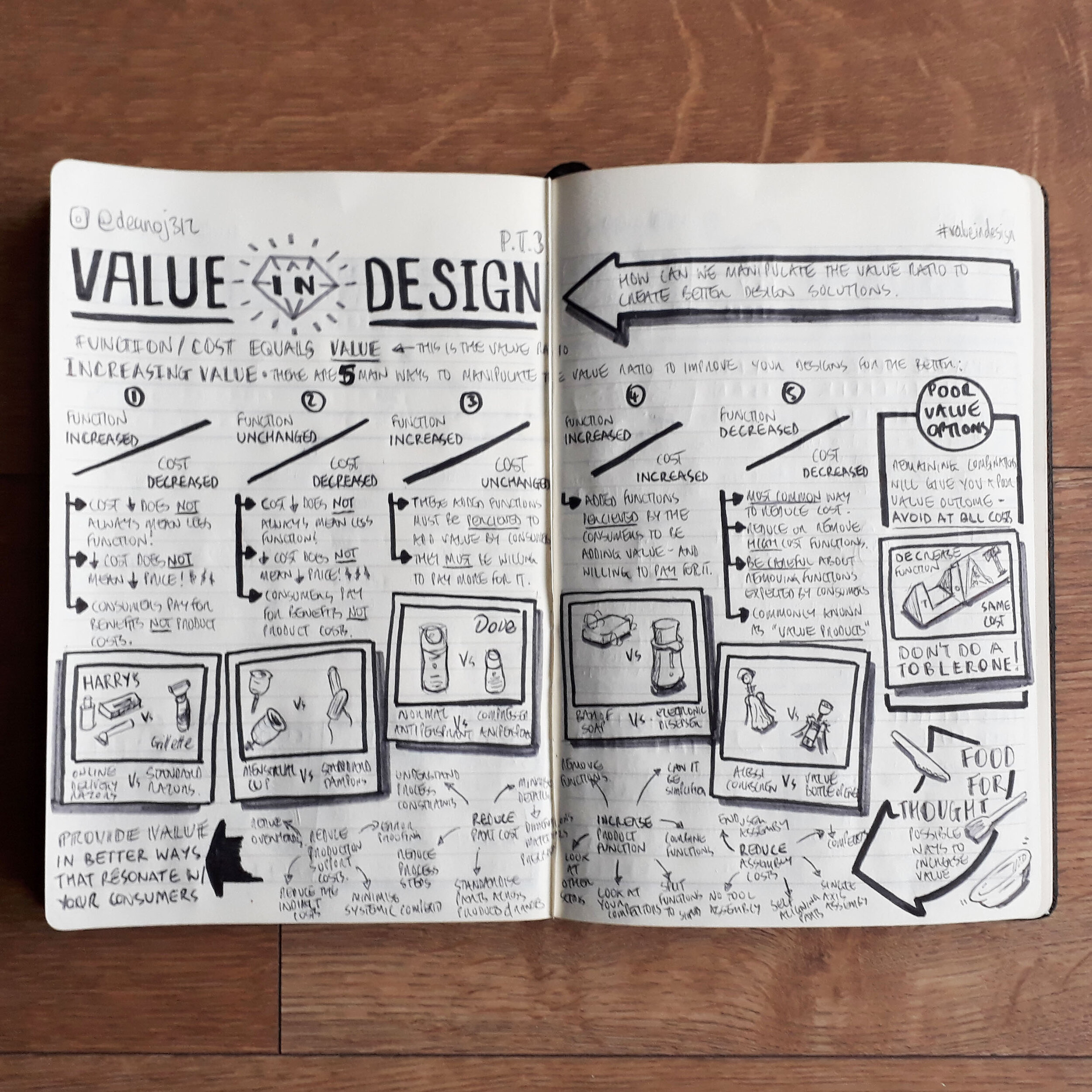

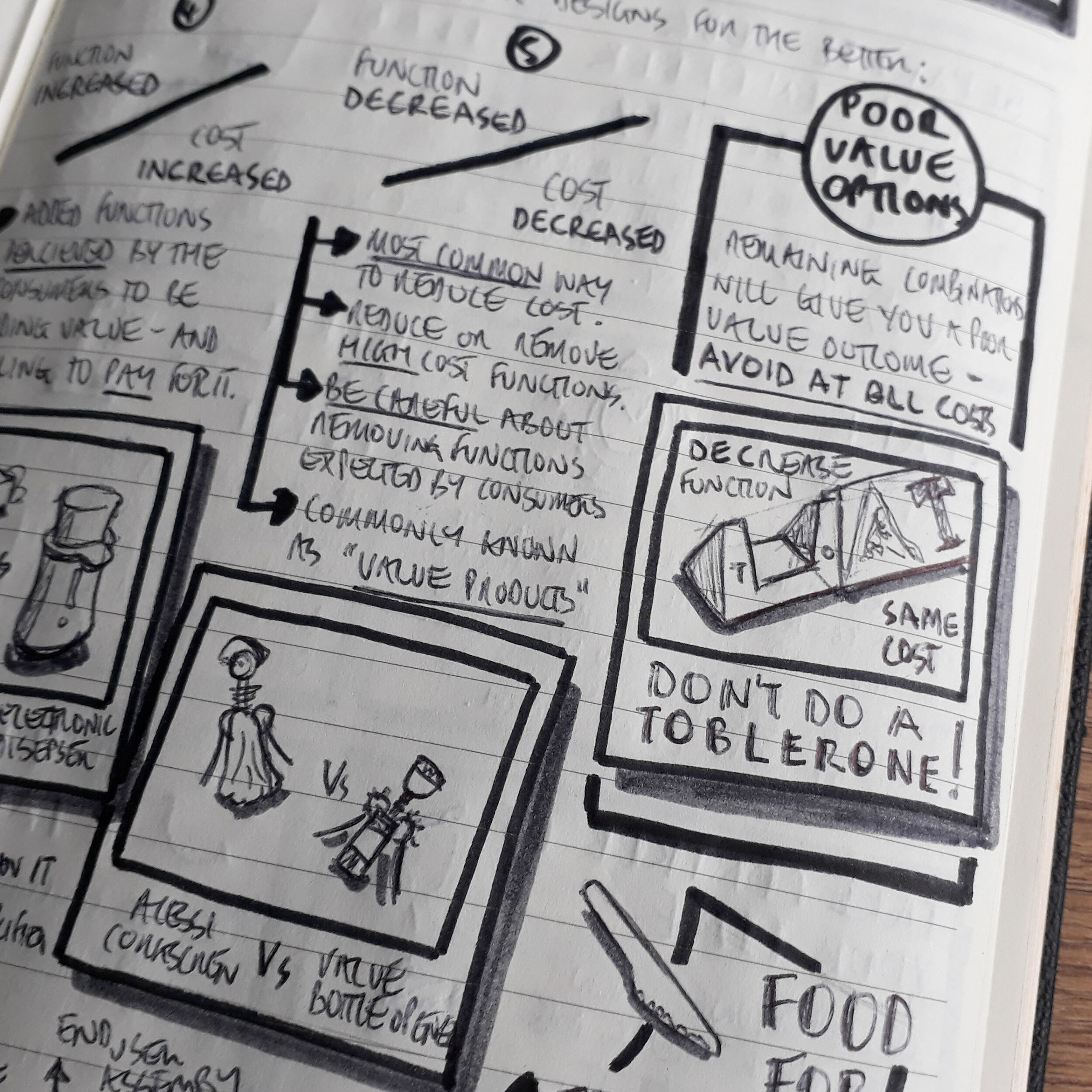

There are five primary ways to manipulate the value ratio for the better:

Function increased / cost decreased

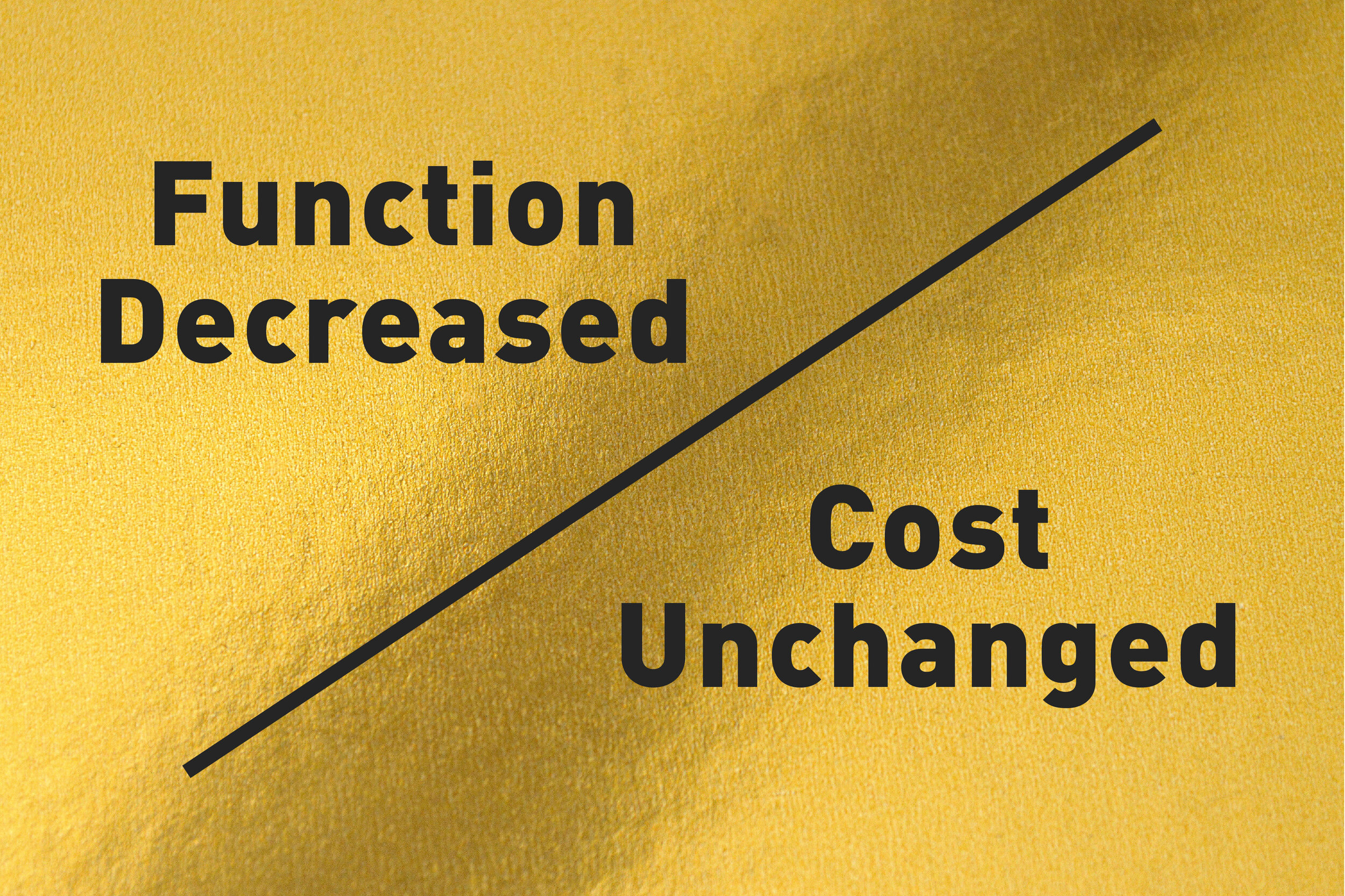

Function unchanged / cost decreased

Function increased / cost unchanged

Function increased / cost increased; and

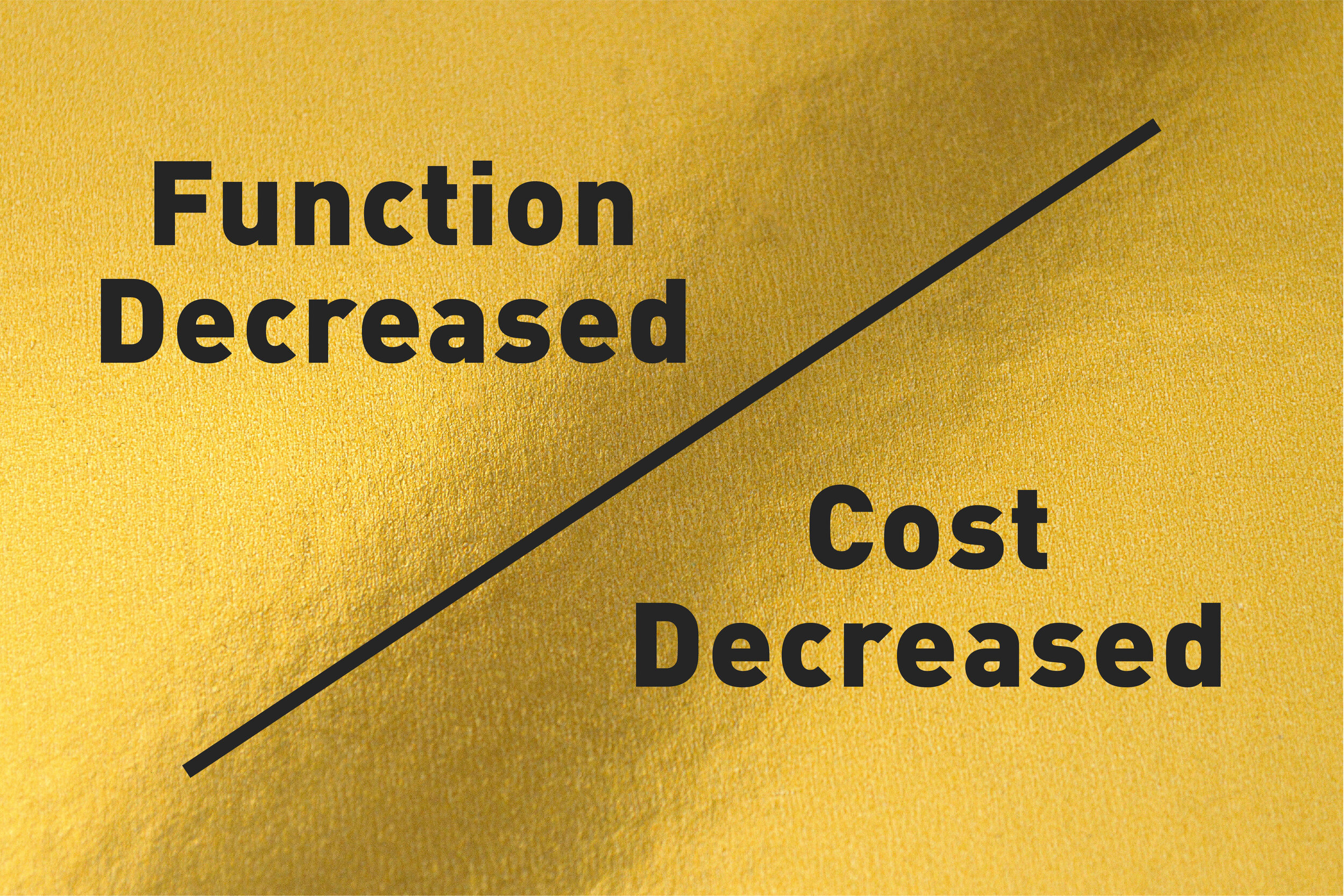

Function decreased / cost decreased

Some of these are easier to achieve than others. In the following section, I will break down these five methods of manipulation, with an example for each.

In an ideal world, I would have liked to have found product examples within the same brand or business, but most of this work is done behind design studio doors, so isn’t available to the public.

I’m still not 100% sure about some of these examples, as I don’t have access to company’s costs and design processes, so if you think of any better examples, please drop them in the comments section below.

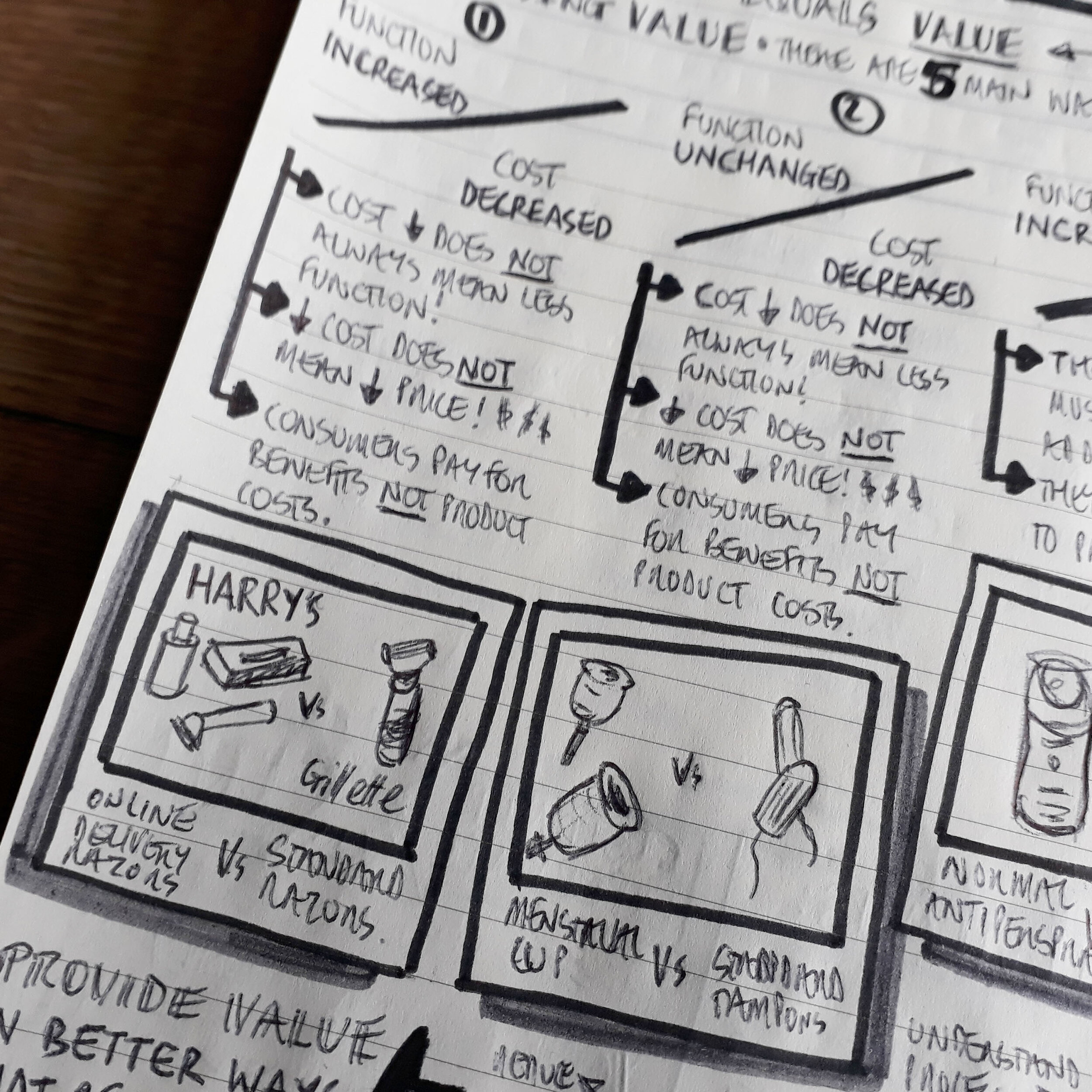

Function Increased / Cost Decreased = Increased Value

Reducing cost doesn’t always mean reducing the price. Cost is how much money it takes for you, the business, to make the product. Price is how much the consumer pays for it.

The money saved from reducing the cost can be added into the profit, or reinvested into further development of the product or its packaging. Similarly, reducing the cost doesn’t always mean a reduction in function.

This is probably the most difficult method of value manipulation to achieve, but it can be done. Remember, consumers pay for value of the benefits of the product, not the products cost.

An example of this can be seen in the shaving market. Harrys, an online shaving subscription service, offers more value to a consumer than more traditional options available in high street stores, with the ability to have products shipped direct to your door, with everything you need for a decent shave. Subscription services are also a great example of instilling customer loyalty, but that’s a talk for another time. Harry’s reduce their cost due to the fact that they own the blade factory that they use to create their razors. The increased function to the customer is the subscription service that Harry’s offer.

Function Unchanged / Cost Decreased = Increased Value

Just like reducing function doesn’t mean that the cost is automatically reduced, reducing the cost doesn’t always mean that the function has to decrease. The two can be influenced by each other, but can also be independent from one another.

Cost can be saved in many ways: renegotiating a better price with your supplier, changing supplier, reducing overheads, using a different type of material...

These kinds of cost-reducing measures sit outside of design, but as production technology and efficiency is always improving, there will always be a way to create a better design solution without affecting the functionality of the product.

Think about being as efficient as possible with your packaging design, for example, to decrease costs in materials, waste and shipping. Or looking at the problem that the consumer is facing with a fresh pair of eyes.

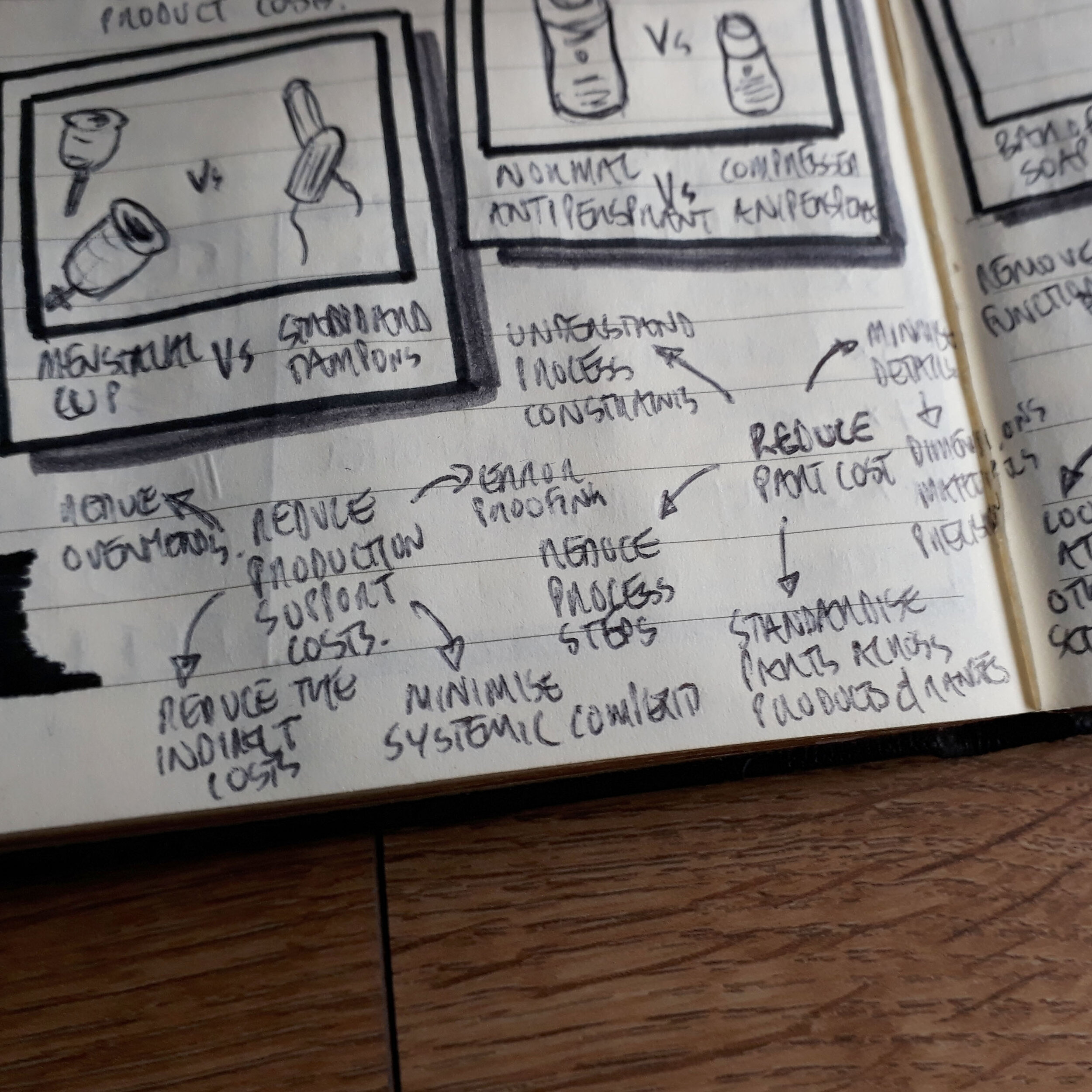

This was a tricky one, but I’ve come up with this example, it takes some explaining, so bear with me: menstrual cups versus tampons. The product function remains the same, but the cost is overall reduced, as the manufacturer is making less individual items within that product category.

For example, menstrual cup manufacturers reduce their cost from the amount of moulds that they need to create their products - usually, there are just three sizes of menstrual cup, compared to the number of moulds needed for creating the variety of tampons available today.

It’s part of a greater social, technological change in the market, and there is an added value from the impact to the environment, reducing the amount of materials used in the manufacturing process, and the complications of the disposal of tampons.

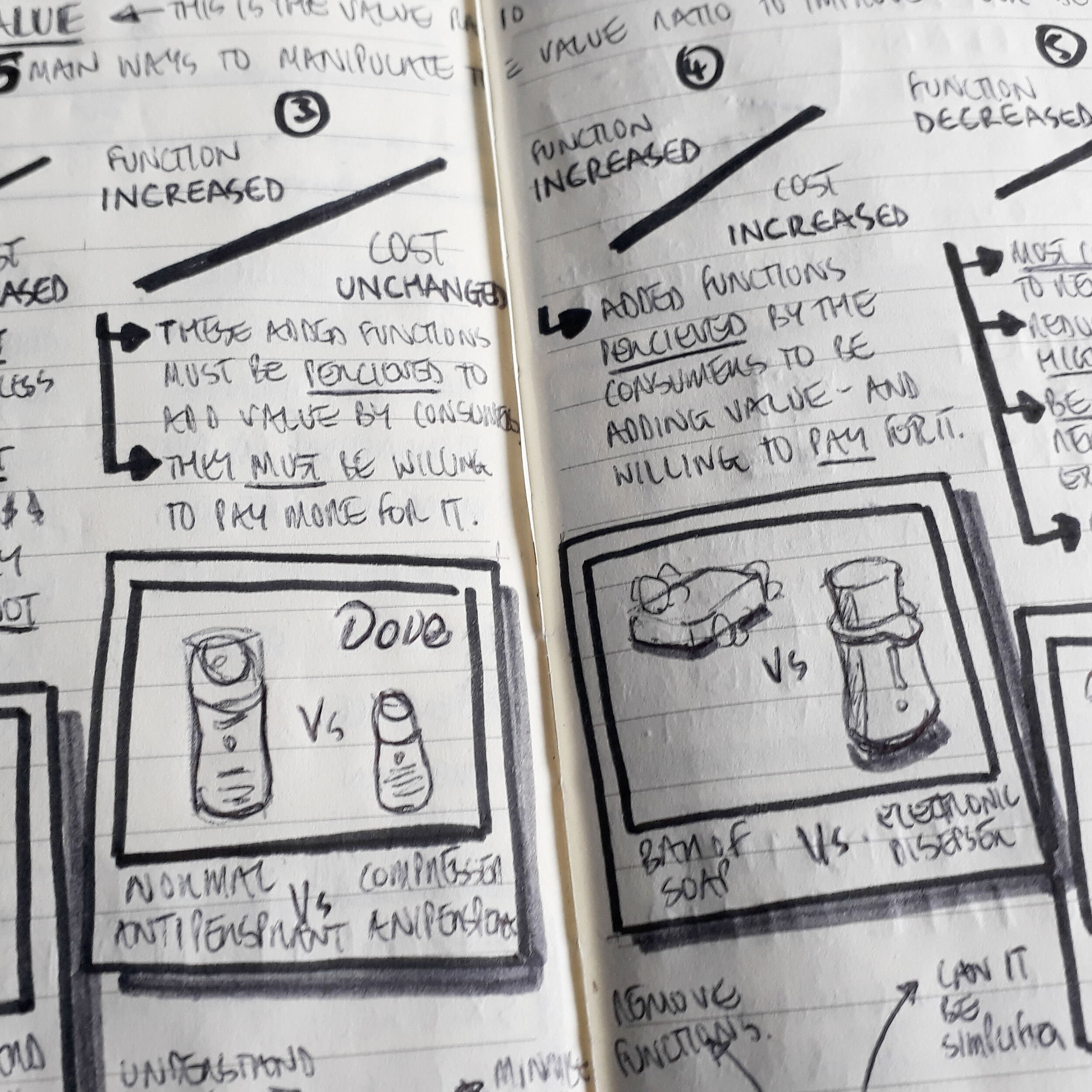

Function Increased / Cost Unchanged = Increased Value

It’s important to remember that when adding new functions, they must be perceived by consumers to be adding value.

These must be communicated effectively to the consumers through marketing and packaging design. This type of increased value is common among commodity products, such as cleaning products ⎯ there’s a seemingly endless stream of new formulations which help improve the product in some way.

One of the best examples of this type of value manipulation is with antiperspirants. A new production technique has recently hit the market, compressing the contents of antiperspirant cans, allowing the producers to sell the same volume in a smaller, more portable can for the same price.

The cost to the manufacturer is unchanged, due to the technological advancement negating the cost saved from the minimal reduction of the materials for the now-smaller can.

Function Increased / Cost Increased = Increased Value

When adding functions to a product, it’s necessary to ensure that the consumer will perceive to be adding value. Sometimes, the customer will be willing to pay for that added value.

The key to achieving this is to have a deep understanding of your consumer perspective on value, and what they actually want to achieve with your product. You must know your customer to know what they want.

An example of this is the difference between a bar of ordinary soap and an electronic soap-dispenser.

The added function of the ‘no-touch’ soap-dispensing combined with the use of technology increases the consumer’s perception of the hygiene of the product, which they would be willing to pay for.

Function Decreased / Cost Decreased = Increased Value

The most common way to reduce cost is by removing function. This is often known as ‘value products’, which aim to reduce or eliminate functions that have high costs.

It is all the more important with value products to manage customer expectations through marketing and packaging to ensure that your consumers don't feel like they have been miss sold a product.

The simplest way to look explain this method of value manipulation is in the kitchen utensils market, where there are levels of value.

At the top, you have designer labels like Alessi, in the middle of the value range, there’s OXO Good Grips and Joseph Joseph, and at the bottom of the value product range, there’s own-brand products, like Tesco.

Poor Value Options

The remaining combinations of the value ratio will give you a poor value outcome, and should be avoided at all cost. An example of this is the now infamous chocolate Toblerone, which changed the product volume to reduce cost, which ended in public ridicule. Don’t reduce the function for the same cost: don’t do a Toblerone!

Now you know the possible ways to manipulate the value ratio for better results.

This final section gives you some food for thought, with a few prompting questions and ideas to consider, empowering you to squeeze every last drop of value from your product for your customers.

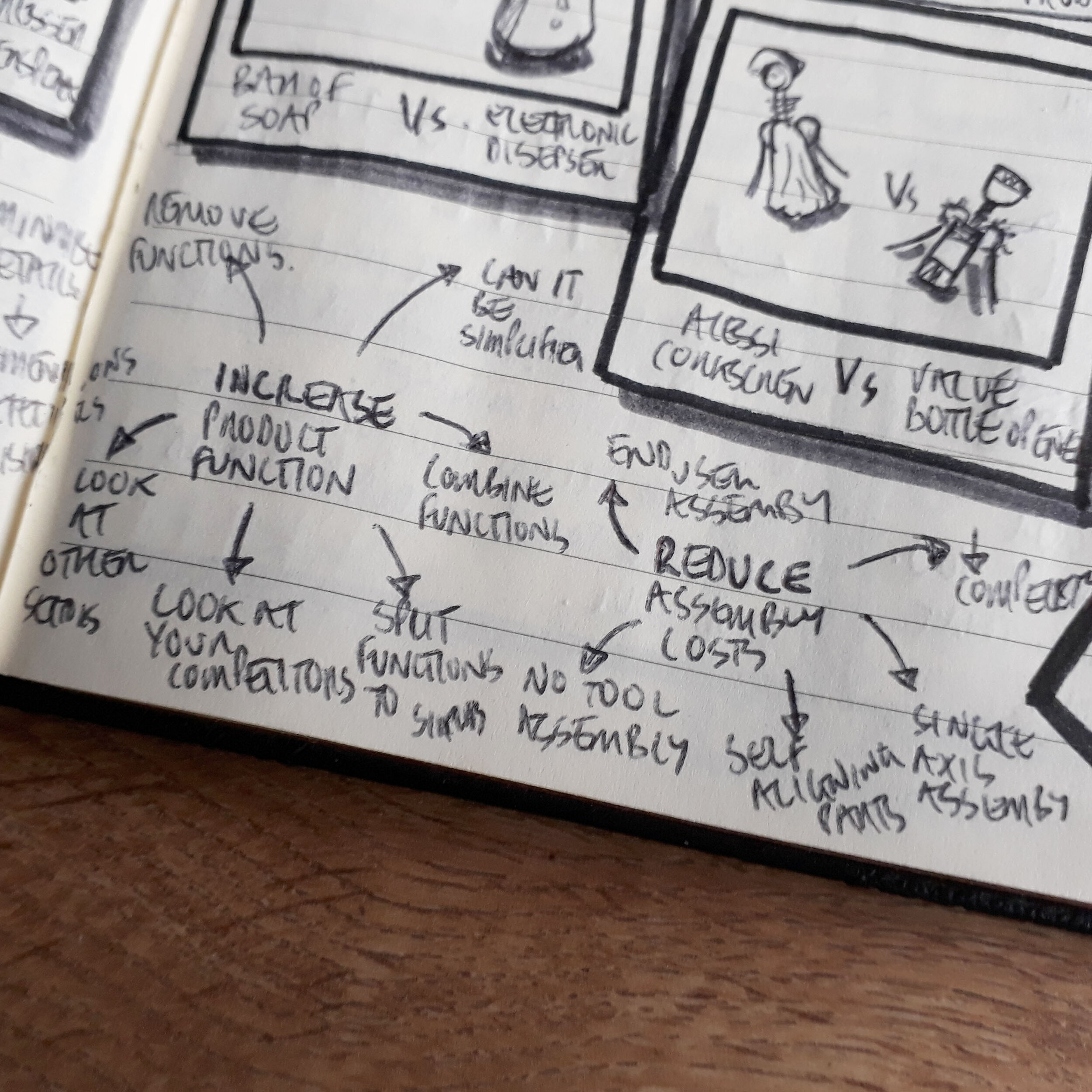

Increased Product Function

Can it be simplified by splitting functions?

Can a function be removed or combined?

What does the competition do?

What do they do in adjacent categories or sectors?

Reduce Part Cost

Read up about your production processes, constraints and cost drivers.

Reduce the amount of production steps to make your product.

Use standardised parts, across products and ranges.

Think about the detailing required in your products parts.

Reduce Assembly Cost

Minimise complexity, combine parts.

Single axis assembly, reduce orientation changes.

Do your parts self-align?

Are there any tools needed to assemble your product?

Consider making that process simpler, and think like IKEA: consider end user assembly.

Reduce Production Support Costs

Minimise the indirect costs and overheads.

Reduce supplies, processes, parts, number of supplier: this is called systemic complexity.

What is your proofing process? How are you going to ensure that the factory follows your assembly instructions?

Now you feel empowered you to better manipulate the value ratio to enable you to create better products for your consumers, clients and buyers.

In this blog article, I have outlined a trail of easy-to-follow breadcrumbs that you can adopt in your own product design, starting with a detailed understanding of categories and linking that to real consumer insights, and how they perceive value when making a purchase decision.

You can now use these insights to manipulate the value ratio to better serve your consumers with designs that fully resonate with them.

It would me a blog written by me without some preparation nudenotes - so here they are:

I also wanted to say a massive thank you to all my sources of inspiration: The Futur Team, packagingsense.com, which is a great packaging blog by Lars G Wallentin. Plus, the countless books I have read over the last few years, especially Creative Strategy and The Business of Design by Douglas Davis. Not forgetting my old university lectures on design in business.